An Artist’s Mystical Journey

Throughout his career, from his early photographs of poor black farmers in the American south to his later African-inspired prints, Professor Emeritus Wendell Brooks has explored his own location within the African diaspora and the experience of black America. Read more about Brooks’ fascinating journey.

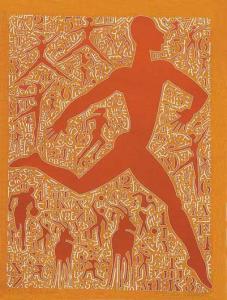

Hello Mr. Louis, 2001

His art professors made him promise he’d never teach. This was perfectly acceptable to him as his goal was to become a master printmaker.

So how is it that this individual has just retired from thirty-six and a half years of an extremely successful career as a teacher at The College of New Jersey—and, despite an enviable reputation as a printmaker, has vowed never to make another print? And in a supremely generous gesture, is donating the vast body of his work, 66 prints in all, to TCNJ?

It’s all part of a journey upon which Wendell Brooks accidentally embarked, a journey begun while on an enforced academic sabbatical following a boyish prank at boarding school. But for his father’s intervention, the sabbatical would have been permanent. (In fact, it is virtually impossible to tell the story of Wendell Brooks without acknowledging the powerful role played by his father—whether he was reacting to, rebelling against, or being inspired by him.) During a two-week suspension to contemplate his errant ways, Brooks drew a landscape. It ended up in the local paper and a vision of his future took root.

An artist’s life would have seemed an unlikely outcome to his early years. Brooks was the son of a high school principal and an elementary school teacher in the small town of Aliceville, AL, and the great-great grandson of a former slave who, after emancipation, was given the classic 40 acres and a mule. Two generations from slavery, Brooks’ father had graduated from Alabama State, a traditionally black college, had started the school at which he served as principal, and had become the go-to guy for both the black and, when issues arose, as they inevitably did in the segregated South, the white communities. As Brooks recalls, “He knew how to play the game.”

While he chafed under the pressure and expectations that came with being the principal’s son, the entrenched racism of the era did not really bother him. “I was not necessarily unhappy at the time with that situation. We basically felt inferior to white people. We thought that all white people were smarter than we were,” Brooks said.

That would soon change. Brooks’ father would leave for Indiana University to get his master’s degree and begin work on a doctorate. He took Wendell, then 12, with him. As Brooks explains, “In Bloomington, the town was zoned off. There was a black side across the tracks and a white side, and on the white side there were two old ladies who owned homes that they’d made into boarding houses. They allowed black graduate students to live there. So that put me in the zone that enabled me to go to the white school. I was the first black student to go to this school. [The consensus was] that I would be happier if I went to the black school, but my dad said no, my son’s in this zone, and that’s where he’s going.”

Lo and behold, it wasn’t long before Brooks “found out that all the white kids weren’t smarter than I was. Plus, I was a pretty good football player, and that helped. Kids used to say ‘Your skin doesn’t look like ours, your hair is like steel wool’ and so on. Later on I would have gotten mad about that.”

Not so much later, he did. The stark difference between the white school in Bloomington and the drafty, undersupplied school to which he returned in Alabama, did not elude the 14-year-old Wendell, and he “started to act out in certain ways.” Although some manifestations of this were good—“I was president of my class, president of the New Farmers of America, captain of the football team, I had the prettiest girl”—all the markers of success in small-town America, Brooks’ father soon dropped a bomb. He was sending Wendell off to boarding school in Tennessee. “[My father] wanted absolute control of the school and the community, but he couldn’t control me,” Brooks explained.

At Morristown College High, a school full of upper-middle class black boys, Brooks was not “the smartest boy there. When I got there,” he remembers with a huge belly laugh, “they voted me best dressed!”

Morristown was a conservative religious school that was not amused by boys’ shenanigans, so it was just as well that it was a newly serious Brooks who returned after his two-week suspension. Having his landscape reproduced in the local paper boosted his self-esteem. He brought a new diligence to his studies and became one of only two boys in his class in the National Honor Society. His hard work paid off with acceptance to prestigious Indiana University. When, in 1957, he returned to Bloomington for the second time, he wasn’t with his father, but his father was with him. “I wanted to be a civil rights lawyer – because that’s what my dad wanted.”

It wasn’t long before art classes were nudging out the pre-law curriculum. At IU, he made As in art, Cs in everything else. Brooks was learning to draw, but when, one semester, all those classes were filled, his adviser suggested that he take a printing class. That class led to his first encounter with a man named Rudy Pozzatti, someone who would help determine the course of Brooks’ life. Says Brooks, “He was a famous printmaker, but he was a real man’s man.” This was important to Brooks, who by then was feeling a growing desire to “be a man” (though at that point he was naïve about the designation’s many permutations). It was also important to his Brooks’ father. Pozzatti was a mentor in every sense of the word, and under his tutelage, Brooks became an extremely accomplished printmaker.

Still, while Brooks’ father had come to accept that law, civil rights or otherwise, was not in his son’s future, he doubted his son’s future as an artist, as well, and felt that Wendell should at least pursue a degree in art education. “So I did get my undergrad degree in art education, graduating by the skin of my teeth”—thus the aforementioned promise to his professors that he would refrain from teaching!

His return to IU for an MFA in printmaking in 1968 was a circuitous one, six years in the making. A scholarship to the Woodstock Artist’s Association, and another to the Pratt Graphic Art Association, helped Brooks hone his craft. A spell as a laborer and a subsequent layoff made graduate school more attractive. Back in Bloomington again, he found he had lost whatever academic discipline he had possessed and left to join the Air Force. There, he figured, it was military discipline “or go to jail.” While he avoided deployment to Vietnam (he was stationed in Crete and Taiwan), he says it was his desire “to be a guerilla, a counterinsurgent … [but seeing that] most of those guys went crazy or were dead, I grew out of my warrior mentality. My brother went to Vietnam, didn’t die there, but he’s dead because of Vietnam. He couldn’t adjust when he came back. A lot of those guys came back addicted to all sorts of stuff.”

A “Dear John” letter received overseas left Wendell depressed. He started “sending back to the states for everything that was free in the magazines so at mail call I’d have something to open. And some organization sent me a copy of James Allen’s book called ‘As a Man Thinketh.’” The message of this small classic is that all one achieves—or fails to—is directly attributable to one’s own thoughts. Its lessons came as nothing short of an epiphany for Brooks. From it, “I learned,” he says, “to control my thinking and to visualize and to use affirmations, to be able to change my consciousness.” Brooks left the service a recipient of the American Spirit Honor Medal, and his positive visualizations allowed him, following his separation from the service, to consider applying for a teaching job at Alabama A&M, even though he held only a BS in art education.

“In those days,” he says, “such a hire was kind of unheard of. But my father remained influential, and he had gone up there looking for teachers and bragging about what an art genius I was.” He soon had a telephone interview lined up for his son—and 15 minutes before the interview was scheduled with the chairman of the art department, Mr. Brooks Sr. had telephoned, impersonating his son. As Wendell understands it, the conversation went something along these lines: Could he teach drawing? “My best subject!” How about art history? “I love art history!” Brooks seems simultaneously amused and impressed by this charade. After all, he’d been a listless art history student at best, but he had married within weeks of his discharge and needed the job.

Always a sharp dresser, when the time came for him to actually put in an appearance at the school, he gave his wardrobe some thought. He’d commissioned seven suits from Hong Kong tailors and for this first meeting chose his “power suit … a gray one I wore with a yellow shirt and a black and yellow tie!” He laughs, remembering.

So there he was, spit-shined, dressed to the nines, summoning up all his military bearing, but he only lasted a year. Living on the pittance that was an instructor’s salary made him realize the necessity of acquiring an MFA and the young couple (who would have a daughter together) took off for Bloomington in a wreck of a car and $300 in their pockets. Once there, Brooks learned almost immediately of the newly created Woodrow Wilson/Martin Luther King Fellowship which, he explains, was designed “to take black veterans of outstanding potential and educate them for non-traditional professions for black people. So I became Indiana U.’s first WW/MLK fellow, one of the first 16 nationally.”

Visualizations and affirmations have a funny way of working out. By 1971, when Brooks had finished his MFA and was starting post-graduate work, things were heating up in the cold Northeast. Trenton State College was not immune to the racial tensions of the period, and, as Brooks puts it, “There was a bit of a ruckus [at Trenton State] with the black students demanding some black professors. At that time, I think there were only one or two…. I wasn’t particularly interested. I had been up here and I didn’t like it…. I had received a lot of good publicity by then—there were very few black people with MFAs—and I wanted to teach at Howard, in DC. Teaching at a black college seemed like the right thing to do.”

But before Brooks heard from Howard, Trenton State called with an offer too good to refuse: He could teach, and most alluringly, the school would make him the master of his own print shop. Another dream realized. Yet, he says, “I still had that inferiority complex that a lot of black people have and a tremendous amount ofanger. I was so angry, I scared myself. I felt guilty about not going to a black college, but a psychologist friend told me, ‘Perhaps this is a higher calling. Not every [black professor] could deal with white students.’ When I first came here, I was extremely militant and talked a whole bunch of stuff that I really outgrew. But to get through the system [back then], you just about had to be militant.’’

Being occasionally confused for a janitor by his colleagues did not help matters. (By now, coveralls, not power suits, were his uniform of choice.)

But for Brooks, work was the answer, was his therapy, was the venue for pouring out the rage. That ceaseless output yielded some extraordinarily powerful prints that capture the African-American experience of the era and remain among his favorites. His dedication is legendary. Colleagues still talk about seeing him in those ink-stained coveralls, heading home in the early hours of the morning to catch a few hours of sleep before his classes began. It was a fertile time personally as well as professionally. Some time after coming to the College, he met his second wife, with whom he had another daughter.

Despite the misgivings of Brooks’ undergraduate professors, teaching became as great a passion as printmaking and he eventually worked his way up to a full professorship. Brooks has written, “My students are my prints—images to be brought to life, works of art in the making.” In his Foundations of Art classes he incorporated interdisciplinary study through the assignment of an essay in response to the questions, “Who am I? Where did I come from? Where am I going?” These essays were then rendered as self-portraits. It was a task that demanded both introspection and an artistic representation of those reflections. In what is perhaps the ultimate compliment a student can pay a teacher, one wrote, “Mr. Brooks inspired me, and I discovered talents I never knew I possessed.”

Achievement followed achievement: participation in dozens of exhibitions and one-man shows; steady sales of his prints (Brooks has donated many others); invitations to lecture; an appointment by Gov. James Florio ’62 to the New Jersey State Arts Council; election to TCNJ’s Chapter of the Honor Society of Phi Kappa Phi. Perhaps the most visible evidence of Brooks’ stature as an artist, however, is that his prints now hang in the Library of Congress (three), the National Museum of American Art at the Smithsonian (two), the New Jersey Council of the Arts (five), and in the Macedonia Center of Contemporary Art (two).

And now he’s retiring—more precisely he’s quitting art altogether. He made the point quite effectively when Sarah Cunningham, the director of the College Art Gallery and the curator of Brooks’ current show, asked if he wouldn’t like to make a final print to cap his life’s work. After a firm but polite “No,” he handed over to her his stencil knife. Its crude, Stone Age appearance (there seems to be duct tape involved) belies its ability to yield such delicate and dynamic images.

“The fact is,” he says, “I’ve devoted my whole life since I was a kid to being successful, and [in the process] I’ve ruined my hand, ruined my elbow, bent my back cutting stencils. I wasn’t what I really am, haven’t had the time to fully blossom. I was what I had to be. I figured out what I had to be and that is what I became.” But why stop altogether? Brooks responds with a parable. “A man was on a journey when he came to a wide river. How can I cross this river, he wondered. So he built a raft, a beautiful raft made of bamboo, and when he got to the other side, he decided it was just too lovely to abandon and he ended up carrying that raft on his back.”

In other words,” he continues, “the tools you need for a journey can become a burden that should be left behind when they no longer serve a purpose. This is true of my art.”

But did he enjoy the art, the teaching?

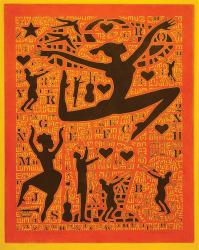

“Oh yes, I enjoyed it. I love TCNJ. I’ve mellowed since I came here. You see, I made a conscious decision to change my personality, to be happy, joyous, free, and that appears in one phase of my work—the dance pieces, for example. No heavy messages there. But in some later pieces, in addition to the central figures, you’ll see some Hebrew letters—I was into Kabala for several years—and those letters would connect me with the power of the creator. But you have to understand, for me, art was a vehicle, [one I] disciplined myself to put first, and was obsessed with. It was the way I coped, it was art therapy, my route to self-discovery.”

Now, says Brooks, it is time for him to direct all his focus on contemplating what he has learned from the major world religions, time to meditate more, to exercise, to achieve a balance of mind, body and spirit.

In short, he says, “I am going to become a mystic.”

Ed’s note: Upon his retirement, Brooks generously donated nearly 60 pieces of his work to TCNJ’s permanent art collection. Those works are on display in the College Art Gallery through February 11. For gallery hours and directions, visit www.tcnj.edu/~tcag/.

- Hello Mr. Louis, 2001

- Professor Emeritus Wendell Brooks

- A Woman Waits for Me, 2001

Posted on January 13, 2009