Ahead of the game

Forty years have passed since Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 was enacted into federal law, banning discrimination against women in education and providing an equal opportunity in athletics. The passing of Title IX, though, wasn’t a quick fix in women’s athletics, because some schools went kicking and screaming over it. TCNJ was shouting about it, too—but over the benefits.

It was the heart of the women’s athletics’ rise nationally at what was then called Trenton State College, and longtime Trenton Times sportswriter Harvey Yavener was interviewing a head coach at an area college. He asked if she would be interested in returning to TSC, her alma mater, to coach, but didn’t get the answer he expected.

“She said something like, ‘Are you kidding? They want to win too much. I like it here, there’s no pressure to win,’” Yavener remembers.

Such a mindset was infectious at what is now known as TCNJ, even if other schools were slow to embrace it. The drive for excellence across the campus helped move women’s athletics at the College to the forefront of NCAA Division III during the early decades of Title IX.

“We were like the poster child,” said football coach Eric Hamilton ’75, today the dean of TCNJ coaches, who watched it all unfold. “You wanted to be like Trenton State if you wanted to be competitive.”

Forty years have passed since Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 was enacted into federal law, banning discrimination against women in education and providing an equal opportunity in athletics. Before Title IX, less than 30,000 women participated in college sports. Today, there are more than 200,000 participants, with more than three million playing high school sports.

The passing of Title IX, though, wasn’t a quick fix in women’s athletics, because some schools went kicking and screaming over it. TCNJ was shouting about it, too—but over the benefits.

From former College presidents Clayton R. Brower and Harold W. Eickhoff, to former athletic directors Roy Van Ness ’43 and Kevin McHugh, to the school’s administration, coaches, and student-athletes, the concept of women’s athletics standing alongside the men was trumpeted throughout the 1970s, ’80s, and ’90s. The 1981 field hockey team followed the 1979 wrestling team with the Lions’ second NCAA championship, and today, 34 of the school’s 40 national team titles are on the women’s side.¹ In addition, there are countless New Jersey Athletic Conference championships, NCAA medals, All-America honors, and other achievements across the board.

“We’ve hung our hat on athletic history in women’s athletics,” Brower says today.

Small steps, then a leap

Of course, it wasn’t always that way. TCNJ resembled a lot of other schools long before Title IX, only taking small steps toward what women’s athletics are today.

As early as the 1930s, the men on campus competed in intercollegiate football, basketball, baseball, and track. Meanwhile, the women competed on a limited scale in intramural and club sports, all the way into the 1960s. That reflected the national climate, even for a TCNJ campus that had more female students than men at what was then a teacher’s college.

There usually was minimal opportunity for female athletes in high school, so the lack of competition at TCNJ didn’t seem out of the ordinary, said June Belli Hemmingson ’56, who played intramural lacrosse. Added Joan Manahan ’62, who played field hockey, basketball, and softball, “I don’t think any of us ever sat around saying, ‘We don’t get to play enough.’ We were happy with what we had.”

Such notions began to change during the 1961–62 academic year. The women were brought to the varsity level in field hockey, basketball, volleyball, lacrosse, and softball, with faculty members Lilyan Wright (also a department chairperson) and Patricia Morris heading up the programs under the wing of the health and physical education department. “Women like to compete the same as men do,” says Manahan, who prided herself on the level of coaching—a prelude to one of the important factors in TCNJ’s eventual national success.

The Lady Lions, or Lionettes, as the women’s teams were called then, later added such varsity sports as bowling, fencing, gymnastics, and swimming. The growth helped TCNJ remain ahead of the national curve in its dedication to women’s athletics. There was enough progress that many of the Lions teams would have enjoyed success even if Title IX did not come along. Once it did, though, the growth was exponential at TCNJ.

The College already had a strong health and physical education program for both men and women, so the elevation of women’s athletics was a natural fit. Van Ness, the athletic director from 1964–87, championed the feeling that TCNJ athletics was a team of men’s and women’s sports, and not separate entities. The feeling, according to coaches, grew without resistance from the men’s athletic programs, which wasn’t always the case at other schools.

“Everybody went to the football games, everybody supported everybody else, everybody worked their butts off,” said Ferne Labati, who coached women’s basketball.

“There was a very strong feeling from my point of view and from the [College’s] Board [of Trustees] as we talked about athletics,” Brower said, “about establishing a firm position on Title IX and having equal opportunities for women as well as men in athletics.”

Big Influences

In 1978, the health and physical education faculty voted to create full-time coaching positions. The coaches who were tenured faculty in the department headed by Ken Tillman had to choose between remaining there as professors, but not as coaches, or relinquishing their tenure and joining the athletics department under shorter coaching contracts. Most of the faculty remained in the PE department, although that didn’t stop influential coaches and/or instructors such as Wright (field hockey, basketball, and lacrosse), Joyce B. Cochrane (gymnastics and PE department classes), and Shirley Fisher (field hockey) from continuing to support the programs and the new coaches.

June Walker and Brenda Campbell were exceptions to the norm. They made the move from the PE department to full-time coaching positions. Walker had taken over the softball program in 1974 and later became associate director of athletics, with the force of Title IX behind her. Campbell, who arrived on campus in 1969, guided the women’s swimming and tennis programs. She even had a bigger budget for women’s tennis than what the Lions men had because the women had proven themselves on a national level, beginning with two-time All-American Kathy (Mueller) Rohan ’78 being named the 1978 national player of the year for all divisions.

That year, Labati was hired from highly successful Immaculata College to coach the women’s basketball team and Melissa (Magee) Speidel came aboard with the field hockey and lacrosse teams, joining Walker and Campbell under the newly created full-time positions. Speidel went on to coach a certain player named Sharon (Goldbrenner) Pfluger ’82, who eventually became her successor in 1985. Labati eventually turned the basketball reins over to Mika Ryan, and TCNJ found itself with a growing cadre of coaches who seemed to be outworking those at other schools.

The coaches were unselfish, fueled by a passionate yet professional approach to their craft, and mostly weren’t looking to use TSC as a stepping stone for a position at a bigger school. Today, Pfluger calls it a labor of love in which the coaches are working for the student-athletes, and not the other way around.

“The late Mr. Van Ness, he had a great knack for just having a feel for who was going to make a good coach and who wasn’t,” Campbell added. “And he wasn’t afraid to go with youth and a lack of experience. If you look back at the coaches that he hired, the phenomenal jobs they did, it was incredible. That was an area [in which] TSC was far out in front of a lot of schools, especially [those that] became Division III.”

“That was really exciting for the women professionally,” Speidel said, “that we were full-time coaches. We as the coaching staff had a bond that this was just sort of the beginning for acknowledging women in athletics.”

Van Ness, who had great loyalty to his alma mater, and Walker were the biggest influences within the athletics department, and they shared a similar vision for the role of women’s athletics. In the decade leading up to Van Ness’ retirement, TCNJ enjoyed an unparalleled level of success among the more than 300 Division III colleges at that time. A former coach himself, Van Ness had a good sense of humor, and he saw the profession as an extension of the classroom, giving his coaches the freedom to shape their programs.

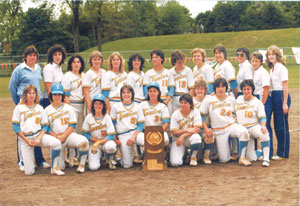

Of course, one of those coaches was the intense Walker, who not only championed women’s athletics in an administrative role but also guided a softball program that posted a 721–154 record, won five NCAA titles, and was the national runner-up seven times in her 22 seasons before she retired in 1995.

“Roy Van Ness, I have to sing his praises over and over again. He was just a visionary,” Speidel said. “He shepherded it, all opportunities, encouraged us, and came to our games. He was sort of the Pied Piper and all of the women were just joining his enthusiasm.”

Walker “was ahead of her time,” Hamilton told Yavener in the Times upon her death in 2001. “A person of conviction, the stone in the shoe that moved Mr. Van (Ness) to make this campus so prominent in women’s sports. She prodded and prodded and shaped what it became, and never wavered.”

Raising the Profile

A myriad of other factors also played in the continued athletic success on campus. When Brower stepped down in 1980, and Eickhoff became president, the College was in the process of raising its academic profile nationally as a leading liberal arts college. The College was enrolling achievers, and in doing so the recruiting base for student-athletes opened to places where many Division III programs could not go.

“We were finding student-athletes who were tops in academics,” Brower said. “But within that group, there were some outstanding athletes as well.”

“The trustees were very clear on how they wanted to see the College develop. Their vision for the institution was to do whatever we do at the very highest level,” said Eickhoff. “Over the process, a very short process, we came to the conclusion that the athletic program had a very good foundation, and that we kind of underlined the development of the College’s excellence in academic areas by making sure that our athletic programs matched that commitment to excellence. And the way we defined excellence—that was kind of easy. If we were going to be excellent, we should be winning national championships.”

And that’s what TCNJ did. While other schools struggled financially to send athletes to national competitions, TCNJ provided the support and brought home the titles.

Lacrosse won the AIWA national title in the spring of 1981, and after the NCAA opened up its doors to women’s sports, the field hockey team followed with a national title that fall. More national titles poured in, with softball gaining its first one under Walker in 1983, having already been the AIWA runner-up in 1980 and 1982. Campbell later guided the women’s tennis team to the 1986 NCAA title, which was the first for a men’s or women’s program in the Northeast.

If Lions teams weren’t capturing NCAA titles, they were claiming national runner-up finishes. And all the women’s teams seemed to have All-Americans at their disposal, many of whom were also Academic All-Americans, including such notables as Tracy Warren ’87, the softball player who now is a national broadcaster, and Kimm Lacken ’88, the all-time leading scorer for TCNJ women’s basketball.

The prestige bestowed on TCNJ was felt beyond the athletic fields. Support was so good that the student body voted for student fees to go toward improving athletic facilities. The most important addition was Van Ness’ vision, the installation of a multi-purpose AstroTurf field, Lions’ Stadium, which opened in 1984. Few schools’ facilities matched the versatility of the turf, on which the football, field hockey, men’s and women’s soccer, and women’s lacrosse teams practiced and played in both good and inclement weather.

Meanwhile, other athletic facilities, which included the Student Recreation Center for general student use, became jewels. Then the Aquatic Center opened in 1987. Each facility provided a recruiting advantage to keep TCNJ athletics ahead of the game.

“I think one of the greatest things [Van Ness] did was get an AstroTurf field,” said Pfluger, who has coached her teams to 11 NCAA titles in lacrosse (including the vacated 1992 title) and eight in field hockey. “We were one of the first [in Division III]. We were playing everybody else on grass for years. I think that was a big commitment. He was very innovative.”

Forever Energized

With innovation came separation from other schools, and that has remained at TCNJ for a long time. Women’s soccer was added as a varsity sport in 1990, and three years later, Coach Joe Russo led the Lions to the first of three Division III women’s soccer titles.

With TCNJ’s blueprint in place, other elite schools in Division III eventually caught up. But the mix of high academic and athletic standards hasn’t wavered, and winning is still a big deal on campus. In fact, the women’s tennis program entered the 2012–13 school year having won all of its conference matches, and all of the titles, since the NJAC (and its previous Jersey Athletic Conference) added the sport in 1982.

In 2011, the field hockey team won another national title under Pfluger, ending a five-year drought for TCNJ athletics, fittingly on the 30-year anniversary of the Lions’ first NCAA title in the sport under Speidel. The 33 NCAA team titles (officially 32 in NCAA records) remain the most among all Division III schools.

“More than Title IX, I just think it was the willingness to put good teams out and look upon sports as something women could have as well as men,” Yavener said. “There is no underestimating how important athletics was in changing the image. Suddenly kids wanted to go there who had never even heard of it.”

“There was so much excitement when we started at Trenton State,” Speidel said. “Title IX provided the opportunity for women to play and compete and it energized all of us. It was this energy that led to our success and put [the College] at the top of Division III women’s athletics. I moved on to coach at Old Dominion in Division I, and there was never the same thrill of being part of the team as at [the College].”

Women’s National Team Championships¹

Thirty-four of TCNJ’s 40 national team championships have been won in women’s varsity sports:

Lacrosse (14): 2006, 2005, 2000, 1998, 1996, 1995, 1994, 1993, 1992, 1991, 1988, 1987, 1985, 1981

Field Hockey (10): 2011, 1999, 1996, 1995, 1991, 1990, 1988, 1985, 1983, 1981

Softball (6): 1996, 1994, 1992, 1989, 1987, 1983

Women’s Soccer (3): 2000, 1994, 1993

Women’s Tennis (1): 1986

¹ All are NCAA titles except for the lacrosse team’s Association for Intercollegiate Athletics for Women national championship in 1981. The 1992 lacrosse title was later vacated by the NCAA.

Posted on December 1, 2012