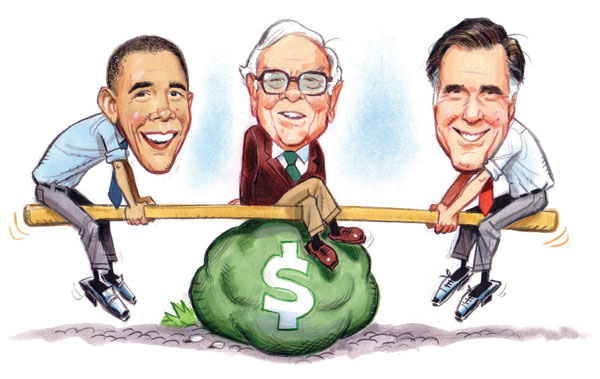

Tax the rich?

Is the Buffett Rule the best way to reduce economic inequality in the United States? We asked a group of faculty experts to weigh in on tax fairness, income equality, and the economic, political, and philosophical implications such a tax code change might have.

Warren Buffett is a man known for his shrewd stock picks. Yet the biggest dollars he ever moves might not be on investment returns, but on tax returns.

The billionaire’s dismay expressed in a New York Times opinion column that he pays a lower percentage in taxes than many of his salaried employees has been picked up by Democrats and morphed into the so-called “Buffett Rule.” As a result, the rich may soon pay more in taxes.

President Barack Obama’s version of the Buffett Rule—a key election-year initiative and the centerpiece of his current re-election campaign focus on “fairness”—would require Americans making more than $1 million a year to pay a minimum effective tax rate of 30 percent on their income. Many millionaires and billionaires pay rates that are about half that under a current tax code that favors investment income over wage or earned income.

In April, a version of the Buffett Rule—the “Paying a Fair Share Act of 2012”—stalled in the Senate after Democrats were unable to get the 60 votes needed to break a filibuster (the vote was 51 to 45). Despite that, the White House doesn’t appear ready to give up on the proposal anytime soon. In an election year, the legislation has emerged as a partisan issue and has met solid Republican opposition.

Democrats are quick to point out that former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney, the presumptive GOP nominee who initially balked at releasing his tax returns, earned $21.7 million in income in 2010 but paid an effective tax rate of 13.9 percent since his income is derived primarily from investments. In the media, Sen. Charles E. Schumer (D-NY) has lobbed accusations that Romney is the “poster child” for why the Buffett Rule is necessary, adding, “it could be called the Romney Rule.”

Associate Professor of Economics Michele Naples said income fairness has become “such a hot-button issue” these days in part because of the Occupy Wall Street movement, and the fact that incomes of the top one percent have skyrocketed over the last 30 years while the incomes of the “99 percent” haven’t risen nearly as much.

But is the Buffett Rule the best way to reduce economic inequality in the United States? Could it help reduce the federal deficit? How likely is it to be passed? And are there better options out there? We asked a group of faculty experts to weigh in on tax fairness, income equality, and the economic, political, and philosophical implications such a tax code change might have.

Show me the money… or not

If enacted, the Buffett Rule is not expected to have any real effect on the lives of the average American and is only expected to make a small dent in the federal budget deficit. Expected revenues would be about six percent of the current deficit spending, or about $47 billion over 10 years, according to a congressional committee.

“I think it’s more of a philosophical issue of fairness than it is one of economic impact,” explained Brian Potter, an associate professor of political science and director of TCNJ’s International Studies Program. “Its practical impact would likely be small. But it would be a symbolic change and one that might resonate with middle-class voters.”

What will the rich people do?

From a macroeconomic ( or “big picture”) perspective, Obama’s Buffett Rule is a “reasonable approach” that would likely cause little damage either to the economy as a whole, or to the Gross Domestic Product or job creation, said Naples. That’s because it doesn’t call for increasing taxes on businesses, which provide real capital formation. Plus, evidence shows that the rich are less likely to spend more money with additional after-tax income than the middle class or poor, she added.

“The conversation here is what does it mean that these rich people don’t get as much money?” continued Naples. “What are they going to do? Are they not going to make financial investments anymore because they can only make 10 percent instead of 15 percent? Are they going to take their finances and go invest in another country? That’s really the debate.”

Is it just a Band-Aid?

Professor Morton E. Winston, chair of the Department of Philosophy, Religion, and Classical Studies and director of the Alan Dawley Center for the Study of Social Justice, called the Buffett Rule “a Band-Aid” that’s not the best way to achieve more fairness. He favors other tax code changes.

“Currently the tax on long-term capital gains is 15 percent—that’s the main reason why people like Mitt Romney, who make most of their income on returns on investments, pay such low taxes,”

Winston said.

“Currently the tax on long-term capital gains is 15 percent—that’s the main reason why people like Mitt Romney, who make most of their income on returns on investments, pay such low taxes,”

Winston said.

Meanwhile, the highest tax on earned income or income from salary is 35 percent. Winston said there’s “a huge discrepancy” in the current code between earned and unearned income. “I just think that that’s completely backwards.”

A better answer? Winston said the tax rate on unearned income should be increased to 28 or 30 percent: “It’s not fundamentally fair for people who work for a living to pay a greater percentage of their income in taxes than those who have made investments or have inherited investments that enable them to live off the income of those investments,” he said.

You want class warfare?

This certainly isn’t the only time in history where great disparities have arisen between the “wealthy few and the poor masses,” Winston noted. “But when people throw around the term ‘class warfare,’ I get really annoyed.”

Real class warfare happened in 14thcentury France when peasants and serfs revolted in what became known as the Jacquerie against lords, with violent results. In one case recorded by the late historian Barbara W. Tuchman in her book titled A Distant Mirror, Winston said a group of serfs attacked a manor house, killed the knight, and “roasted him on a spit in front of his wife and children.”

“That’s class warfare…what we have in this country is class struggle,” Winston said.

An October 2011 Congressional Budget Office report showed that the income of the top one percent grew by 275 percent from 1979 to 2007, while the income of those in the bottom 20 percent grew by only 18 percent during that same period. Meanwhile, the top 10 percent of Americans now control two-thirds of the nation’s wealth, and the richest 400 Americans control as much wealth as the bottom 50 percent of all households combined, Winston said.

“This is pretty extreme income and wealth inequality, and that’s what’s driving a lot of the discontent,” Winston said.

He added that some politicians have argued that lower taxes on the wealthy help stimulate economic growth.

“That’s sort of been the mantra of the Republican party, but in fact it’s just not true,” Winston said. He cited the work of Rutgers University professor and economic historian James Livingston, who gave The 2012 Alan Dawley Memorial Lecture at TCNJ in February 2012 and wrote about the topic in a book titled Against Thrift: Why Consumer Culture is Good for the Economy, Environment, and Your Soul. In it, Winston said, Livingston provides “evidence from economic history that shows that the idea that reducing taxes on the wealthy stimulates prosperity and economic growth is simply not borne out by the facts. What does create economic growth is consumer spending and government spending—those two are the real drivers of economic prosperity.”

Is some disparity good?

When it comes to economic inequality, Potter said there’s some debate about just how much is good or bad. The “supply side” argument is that it’s good to give the wealthy more money because “their investments will trickle down to the rest of us,” he said.

Generally, some inequality is inescapable and might help spark economic growth, but large disparities hurt economic growth, according to Potter. The reason? “Large disparities in resources limit competition, which in turns lowers economic growth.”

Potter, who studies Latin America, said research has shown that highly unequal countries such as El Salvador do not grow as quickly as more egalitarian ones, such as Chile. Also, the region’s years of highest growth (the 1960s) came when economic disparities were minimized, while growth slowed after the neo-liberal reforms of the 1990s and 2000s.

From a more historical and intuitive perspective, Potter said other countries with large political-economic disparities have grown at a slower rate than more egalitarian ones. Some Caribbean and Latin American countries were wealthier, yet more unequal, than the United States 200 years ago.

“They limited education and job opportunities to the elites, neglecting the masses,” Potter explained. In contrast, the United States extended voting, education, and opportunity to a broader percentage of its citizens. That broader participation and widespread economic competition “propelled the United States economy” while unequal policies elsewhere “limited their growth,” Potter explained.

Are there better options?

Andrew Carver, an associate professor of finance and international business, said he thinks the Buffett Rule is politically motivated rather than policy “based on sound economic reasoning” since it is “effectively an increase in taxes on capital gains.”

Carver said there’s a logical reason why capital gains rates are lower than marginal income tax rates. That’s because increasing capital gains tax rates above the levels where they are now often doesn’t result in higher levels of revenue for the government because earning a capital gain is a discretionary act by a taxpayer.

“It’s very easy to avoid the capital being taxed just by choosing not to sell an investment, and that’s one of the reasons why it’s so difficult to make estimates of how much revenue this tax would create because it’s difficult to estimate how taxpayers would respond to higher marginal tax rates,” Carver said.

“It’s very easy to avoid the capital being taxed just by choosing not to sell an investment, and that’s one of the reasons why it’s so difficult to make estimates of how much revenue this tax would create because it’s difficult to estimate how taxpayers would respond to higher marginal tax rates,” Carver said.

Carver, who previously worked as an equity research analyst at Morningstar Inc. covering the banking sector, said the Buffett Rule “doesn’t bring a lot of benefits and has potentially significant costs.” In addition to not raising much revenue, Carver said “because this is effectively a tax on wealthy people changing their portfolio, like other taxes on economic transactions, it may reduce the propensity for people to move their investment dollars toward different opportunities.”

“This isn’t a good idea if we want capital to be flowing from unproductive investments to new and better opportunities,” Carver said. “For example, you want entrepreneurs to have the ability to raise the money they need to start new companies, so increasing capital gains tax rates could inhibit the flow of money to new businesses and have the effect of hurting economic growth in the long run.”

Winston said the better answer might lie in letting the Bush tax cuts expire at the end of 2012—a move that could bring in $1 trillion over the decade, according to some estimates.

Carver said such a move had the potential to be “really big” in terms of revenue and economic incentives: “We’re talking about marginal taxes on income and marginal tax rates on capital gains and dividends.” But he cautioned, “There are a lot of angles that need to be looked at overall in terms of how we handle tax policy for the next four years.”

But could it pass?

Most Americans, including Romney supporters, favor a higher tax on the rich. A January 2012 survey on spending and tax priorities conducted by the Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy at Washington University in St. Louis found that 93 percent of Obama supporters and 67.8 percent of Romney supporters said taxes should be raised on those earning more than $1 million a year. The survey included responses from a random sample of about 1,350 eligible voters.

While the survey didn’t ask in detail about the Buffett Rule, “the American public clearly favors higher taxes on high-income taxpayers,” Steven S. Smith, director of the Weidenbaum Center, said.

So could the Buffett Rule become law anytime soon? Carver said he doubts it “will ever see the light of day,” particularly because of the Republican-controlled Congress.

Potter doubts anything will happen until after the November 2012 elections and January 2013 inauguration because “Congress has gotten very dysfunctional and it’s hard to predict what they will do.” If President Obama were re-elected, Potter thinks the Buffett Rule could have a good chance, particularly if there are Democratic gains in the House of Representatives and because members of the Tea Party, who are interested in closing the deficit, may be swayed.

Naples remains optimistic.

“A lot of people are feeling the pinch in the hard times,” Naples said. “And the claim that it’s class warfare to make the richest pay the same as everybody else not only is not going to fly, but it’s going to end up turning things upside down.”

She added that 50 years ago, most U.S. citizens considered themselves middle class, whether working class or professional, and enjoyed what they believed was a classless society. Now, that’s all changed.

In the end, Naples said: “The presumption of the very well-off that they are exempt from the basic civic responsibility to pay taxes because they are rich sounds more like aristocracy than democracy.”

Illustrations (c) Dave Arkle.

Posted on June 7, 2012