Great Expectations: How “Titanic” Burst the Wireless Technology Bubble

Millions of Americans thought trans-oceanic travel was safe thanks to wireless telegraphy. The sinking of the world’s most famous ship proved them wrong.

by Alexander B. Magoun and John C. Pollock

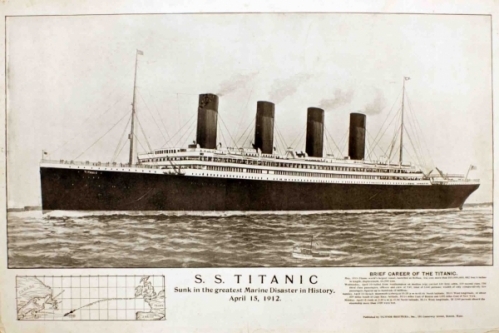

When wireless operator and future head of RCA David Sarnoff confirmed that Titanic had sunk and taken 1,500 people with it on April 15, 1912, the news shocked tens of millions of Americans, who thought trans-oceanic travel was miraculously safe. They had been reading, seeing, and hearing about the wonders of wireless telegraphy on the high seas in fiction and fact for five years through that era’s mass media—magazines, newspapers, theaters, movies, amusement parks, and books. As a result, members of the public assumed, wrongly, that the ability to communicate through mysterious, expensive, or “high” technology brought with it security, reliability, and implicit system regulation.

Who was responsible for this illusion? The unwitting culprits included short story writers filling the bottomless chasm of content for national magazines; multimedia entrepreneur Frederic Thompson, the wizard behind Coney Island’s electrified phantasmagoria, Luna Park; and Marconi wireless operator Jack Binns of the sinking ship Republic. Joined serendipitously, if not by financial interest, they used radio in stories to promote the safety of ships in distress, despite widely reported failures of wireless technology in other applications. But none of this diminished the allure of the mysterious technology offering action at a distance.

Who was responsible for this illusion? The unwitting culprits included short story writers filling the bottomless chasm of content for national magazines; multimedia entrepreneur Frederic Thompson, the wizard behind Coney Island’s electrified phantasmagoria, Luna Park; and Marconi wireless operator Jack Binns of the sinking ship Republic. Joined serendipitously, if not by financial interest, they used radio in stories to promote the safety of ships in distress, despite widely reported failures of wireless technology in other applications. But none of this diminished the allure of the mysterious technology offering action at a distance.

Start with the most successful writer about wireless, Edwin Balmer. In 1907, he published three stories in the popular Saturday Evening Post, which involved heroic young men using radios to rescue their sinking craft, save the country, or arrest a criminal onboard—Caught by Wireless also became a movie the next year. Learning of impresario Thompson’s love of staged disasters, Balmer sold him a scene of a lone wireless operator narrating messages from and to a shipwreck through his noisy spark transmitter. In the summer of 1908, Thompson staged Via Wireless for Luna Park’s millions of visitors to great effect, and commissioned two playwrights to turn it into a four-act drama involving a steel mill, naval cannon, and a love triangle. It opened at the 1,000-seat Liberty Theatre on 42nd Street in November. It played right up to the day that S.S. Florida rammed R.M.S. Republic in a fog off Nantucket. Republic’s wireless operator, Jack Binns, contacted several stations, and the Baltic rescued 750 passengers and crew from a ship that one observer thought “unsinkable.”

The modest Binns became a reluctant celebrity, celebrated by newspapers large and small across the country and feted with a tickertape parade in New York City. Music publishers offered songs about him and the safety of wireless, and Vitagraph Pictures recreated the story less than a month later. By late February, models of the ships were colliding in a steamy tank so realistically that many who saw the collision on screen wondered how it was possible. Binns spent most of the year touring with the Via Wireless roadshow, pushed by his employer Guglielmo Marconi, who needed more business, and pulled by Thompson, who offered far more than his $12 a week salary. It played every major city in the country; President Theodore Roosevelt was in the audience in Washington, D.C. Saved by Wireless returned, without Binns, to Luna Park in 1910 and continued to the British empire. Meanwhile, Thompson turned the play into a syndicated newspaper series for cities not big enough to attract the show. Balmer also profited, turning one of his other stories into a novel in 1911, and expanding the third into a novella for The Popular Magazine.

Real life stories and fantasies like these–commingled in the minds of media producers and consumers and confounding fiction and truth over a hundred years ago–remind us that the separation of news and entertainment is rarely pristine. Great suffering can ensue from unrealistic assumptions and expectations about working systems, safety regulations, heroic humans, and happy endings.

Indeed, the sinking of Republic forced a reluctant Republican Congress to pass the Wireless Ship Act in 1910, requiring shipping interests to pay for shipboard wireless stations and outsourced operators. It also aligned the U.S. with the second International Wireless Telegraph Convention of 1906 by mandating that all ships respond to others’ messages; assign priority to SOS “distress calls”; and provide for unlicensed but “skilled” operators.

Titanic made it apparent that this was not enough, resulting in further international regulation and domestic legislation in the summer of 1912. Since then efforts to increase wireless reliability have resulted in more complex, satellite-based distress-call systems that alternately exclude radio operators and assign more responsibility to ships’ captains. As Costa Concordia’s accident last January shows, regulation and higher technology will never exclude the frailties of the human factor.

John C. Pollock is professor and chair, Department of Communication Studies at The College of New Jersey, where the Sarnoff Collection currently resides.

Alexander B. Magoun is outreach historian for the IEEE History Center in New Brunswick, NJ, and former director of the David Sarnoff Library and Museum.

The wireless telegraph key on which David Sarnoff received and transmitted news of the Titanic disaster is one of the highlights of TCNJ’s Sarnoff Collection. With more than 6,000 artifacts originally housed in the Sarnoff/RCA research laboratories Princeton, the Sarnoff Collection documents the major developments in wireless communication and electronics in the 20th Century. The collection will soon be available online and on exhibit at TCNJ.

Posted on April 25, 2012