Running with the Coatman

Meet the king of the stunt runners: Dennis Marsella ’75, aka the Coatman. Since 1981, Marsella has completed more than 120 marathons in some of the most counterintuitive running garb imaginable. Yet underneath the showman is an intensely serious runner.

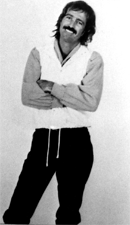

Dennis Marsella is not like the rest of us. At age 60, his hair is conspicuously dark, and he believes he’ll never get old—at least not in the traditional sense. He’s risked death by heat exhaustion in the name of his passion. He likes to figure out how something should be done and then do it the hard way, better than anyone else. He learns the rules and then breaks them.

Marsella, a 1975 graduate of the College, is one of the country’s greatest stunt runners. They call him Coatman.

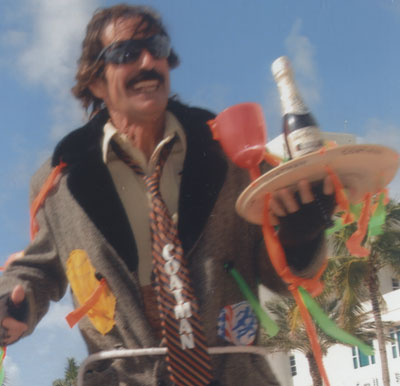

Since 1981, Coatman has completed 128 marathons (26.2 miles)—four or five a year—in some of the most counterintuitive running garb imaginable. When he runs, he wears a winter coat, big tie, and dress shoes, and carries a tray topped with a bottle and glass, waiter-style. Marathon fans await his appearance and cheer for him on the streets of Los Angeles, Miami, and New York, where he has guaranteed entry to the New York City Marathon.

To qualify as a stunt runner, Marsella explains, one must either wear something or carry something that makes it considerably more difficult to finish the race. Check and check.

“I have never run with anyone who’s done both,” he says. His wardrobe has evolved over the years—he added the tray, once a pizza box, in 1993, and says it’s become “the star of the show”—but it all started with the coat. At age 29, never having run more than a few miles at a time, Marsella saw a photo of a man crawling to the finish line of a marathon. He decided to give it a try. Three days before the race, he had a crazy idea.

“I said, you know, the most ridiculous thing you could do in Miami is to put on a coat and run,” he says. A former high-school wide receiver, he decided he wasn’t lightweight enough to top the ranks of traditional marathon runners. “Why don’t you just bring out the best in you?” he asked himself. And so, in spite of Miami’s sizzling climate, Marsella donned the denim jacket he had taken with him when he moved to Florida from New Jersey. Coatman was born.

The secret of “psy-running”

Three decades and four coats later, Marsella is as relentless as he’s ever been, and running has become more central to his life than he ever imagined it could. Coatman’s lifestyle has taken on a couple different layers. Obviously, there’s the entertainment value: Stunt runners offer a welcome distraction from the monotony of the race.

“It’s satire. It’s like seeing Saturday Night Live,” Marsella says. Coatman and other costumed runners playfully take the wind out of the competition, all while running the full length of the course themselves. “Even though it’s very difficult to do it, it’s also funny,” he says.

“Most of the spectators at a marathon are there to watch somebody they know,” says Bart Yasso, chief running officer at Runner’s World. Though he doesn’t understand what would drive anyone to run in a winter coat, he admires what Marsella does. “Everyone kind of looks the same at some point,” Yasso says. “Coatman does not look the same as everybody else.”

It’s hardly surprising that Marsella plays the part of a trickster. His most pronounced memory of campus life involves planting speakers in the windows of his Wolfe Hall dorm and blasting the Rolling Stones’ “Sympathy for the Devil.” Everyone heard the rock ’n’ roll echoes, he remembers, but no one knew where it was coming from. “I used to laugh my head off,” he says.

Yet underneath the showman is an intensely serious runner. Marsella runs every day, peaking weekly or biweekly at around 20 miles, and he estimates he’s racked up more than 108,000 training miles since he started. He enlists a strategy he calls “psy-running” or “Bodhisattva running,” which combines Eastern breathing and concentration techniques. His special technique, he says, is the reason for his superior endurance and his unusually young appearance. He maintains that he has never once been injured by participating in sports.

“Honestly, it’s like my religion,” he says. “I do the breathing when I run, and I also do certain visualizations. You have to visualize the energy flowing around your system.” Though Marsella studied traditional psychology at the College and says he was initially “like an atheist scientist,” he started reading books about consciousness in the late 1980s. In between his intense running workouts and his night job as a security officer, he studies physics and parapsychology—the researching of “altered states.”

On subjects like these, Marsella can expound at length. “It is being studied in a scientific way, [though] it sounds like it’s not scientific,” he says.

A card on his jacket bears the word “Bodhisattva,” which Marsella says is an enlightened being, “reincarnated to help humanity.” In coordination with his visualizations, he inhales extra amounts of air when he runs, holds it in for half a minute, then exhales, flooding his body with oxygen.

“Most guys do it sitting in meditation,” he says. “I do it as I run.”

The next Paula Abdul…almost

Coatman’s denim namesakes have stories to tell. His coats have taken on red ribbons, sewed-on souvenir patches, and holes and tears from wearing and washing. “Every time I washed it, it got holes,” he says. “There’s something with denim.” He wears it anyway. His newest coat, he says, is probably the warmest yet.

Marsella and his coats have been featured in newspapers across the country, in Runner’s World, and on CBS. They are artifacts of the wear and tear he’s taken over the years. Despite not having been injured, he says, he’s gotten knocked around by other runners and has on more than one occasion, unsurprisingly, succumbed to the power of heat.

“That one is the factor that can kill you,” he says. During one Los Angeles Marathon, he blacked out on the side of a road in Hollywood. When bystanders summoned him awake, he told them he’d only had a cramp and leapt back into the race. “I know that if I give myself two, three minutes, I can come back,” he says.

Marsella’s souvenirs recall happier memories. One of his patches depicts an American flag and a Soviet flag joined together, enveloping a pair of silhouetted runners. It commemorates what he calls the biggest marathon of his life—the 1987 Moscow International Peace Marathon. “The Russians went nuts. I ran in my coat and it hit 80 (degrees) that day,” he says.

“That was a great course. It went through Gorky Park and through the Kremlin and Red Square and Lenin’s tomb,” he recalls, where, he points out, the embalmed Soviet leader remained agelessly preserved.

Coatman could have been “the next Paula Abdul.” In 1992, L.A. Gear—the shoe company known for its late-’80s rise and subsequent slide into bankruptcy—flew Marsella to Los Angeles for dinner and a photo shoot and presented him with a coat labeled “Coatman.” The company was still riding relatively high then. Pop stars such as Abdul and Michael Jackson were promoting L.A. Gear shoes. Had the tête-à-tête led to something more, Coatman might have been the next voice of one of the nation’s biggest shoemakers.

Nothing came of it. But after Jackson and the company sued each other and L.A. Gear’s stock plummeted, Coatman kept on doing his thing, endorsement or no endorsement.

Last man running

He seems to have outlasted them all: the “zanies” in New York who run as robots and clowns, the Perrier bottle man who lasted three years, the Elvises and Wolfmen who run the first mile or take turns. “I’ve never seen any stunt runner last more than 10 years,” he says.

What’s more, he shows no sign of stopping. That would be very un-Coatman-like. “I have no injuries. I honestly can’t imagine not being able to run marathons,” he says. “To me, I should be able to do this at least another 20 years.” He lists his times in the lower four-hour and upper three-hour range. He ran the New York City Marathon in 4:12 last year and 3:59 the year before. “He’s running them at a pace that’s kind of in the median time for people his age, or even faster,” says Yasso. “He’s adding that degree of difficulty, so you’ve got to hand it to the guy.”

Stunt runners, who constitute a small portion of the competition, are not taken very seriously, according to Yasso. He’s convinced Marsella is in it to be recognized—that’s the only way the Coatman stunt makes sense to him. Still, he can’t help but respect the legacy of the denim-clad dynamo. He says Marsella is “the real deal.”

“(It’s) amazing to me. There have been some others out there that kind of come and go, but the Coatman’s been steady,” Yasso says. “I’ve seen this guy for 20-plus years, and he’s not going away.”

To date, Marsella says he’s made about $10,000 from his running career—not an insignificant sum for a stunt runner. And his ambitions are as strong as ever: “If I keep doing this another 20 years, I don’t see how I can’t make a million dollars with some company doing something.”

“You see all these fake characters doing advertising,” he says. “How can I not be worth money if I’m a real character?”

Posted on November 7, 2011