TCNJ Art Gallery exhibition rethinks representation of black men

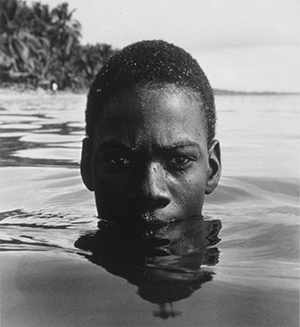

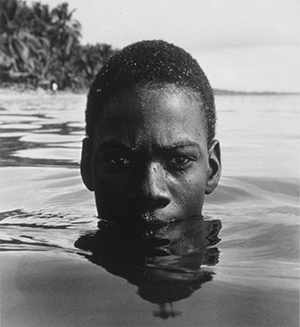

“Wounding the Black Male: Photographs from the Light Work Collection” explores the visual exploitation of the disfigured black male body and the ways in which artists disrupt this problematic paradigm.

by Stephanie Shestakow

This spring, TCNJ Art Gallery presented the thought-provoking exhibition Wounding the Black Male: Photographs from the Light Work Collection. Curated by Gallery Director Sarah Cunningham and Associate Professor of English Cassandra Jackson, the show featured 31 photographs exploring the visual exploitation of the disfigured black male body and the ways in which artists disrupt this problematic paradigm.

As viewers confronted themes of violence, sexuality, spirituality, and topics such as slavery, they were challenged to think about the artists’ strategies for depicting black men. Through the accessible medium of photography, the gallery invited visitors to ask critical questions about representation and race.

The project originated in spring 2007 when Jackson, who was researching the book upon which the exhibition is based, spoke at a campus Politics Forum. (Her book, Violence, Visual Culture, and the Black Male Body, was published by Routledge in 2010.) Cunningham was in the audience and recognized that the two artists Jackson addressed most were once affiliated with Light Work, an artist-run, non-profit arts organization located in Syracuse, New York. Light Work supports emerging and under-represented artists working in the media of photography and digital imaging, and remains one of the most important sites in the United States for the production of contemporary photography. Both colleagues were excited about the prospect of an exhibition formed from this groundbreaking collection.

Selecting appropriate images from the collection, and using ideas from Jackson’s writing as a framework, a provocative and critical illustration of black masculinity was born. Cunningham commented: “The goal was not just to create an exhibit to illustrate Cassandra’s book. We also wanted to apply her theories and build on her research.” This was accomplished by extending Jackson’s analysis to a variety of Light Work artists who dealt with the black male body. Each artist in the show captured the notion of reclaiming the wounded black male from the violent representation that has reverberated throughout our culture.

The photographs in Wounding the Black Male range from portraits to still lives, some with no “real” people in them at all. Take Hank Willis Thomas’ and Olujimi Kambui’s stills from a video called Winter in America. There are no actual bodies but instead action figures that portray the murder of Willis’ cousin outside a Philadelphia nightclub, a commentary on the extent to which violence permeates our culture. In Albert Chong’s Self-Portrait with a Baboon Skull, 1994 (1995), the artist combines found objects with his own image that speak to his Asian, Caribbean, and African roots and make us consider the routes of the slave trade and how it shaped the African Diaspora.

Several artists subvert the notion of the wounded black male by placing black men in iconic roles. Renee Cox’s Pieta, David=The African Origin of Civilization, and Atlas (all from 1995) put black figures in codified and widely recognized images from Western Civilization. Three black-and-white photographs from Max Kandhola’s The Seven Last Words of Christ 1997–2002 depict the head of a man, eyes closed, whose spiky hair evokes a crown of thorns. Jackson sees the image as a reflection of the 19th-century notion of the black slave (such as that found in Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin) who takes the blame and sacrifices himself for others.

Another disrupted black masculine stereotype is the idea of the absent father. In her series The Father Project , Ellen M. Blalock creates compositions that reveal the intimacy and love of the father-child relationship. Skylar (2002) and Jermane (2002) capture the tenderness and love expressed by these young men in a direct and touching way.

Jackson acknowledged the omission of visual historical evidence (such as pictures of slaves or lynchings) from the exhibition, as these images ran the risk of reenacting the violence. The contemporary works in the show alluded to the history of racial violence, but at the same time posed serious challenges to the oppressive racial ideologies that caused that violence. Jackson explained: “Because many of the 19th- and early 20th-century images of wounded black men were designed to impress audiences with the ideology of white supremacy/black inferiority, any reproduction of these images risks disseminating those kinds of ideas.”

Wounding the Black Male epitomized Cunningham’s vision for the TCNJ Art Gallery as teaching instrument and place of innovative cross-disciplinary collaboration. Taking faculty research and ideas deeper through gallery exhibitions enriches the artistic, cultural, and intellectual life of the campus community and beyond.

Posted on April 13, 2011