Crossing Borders to Create Community

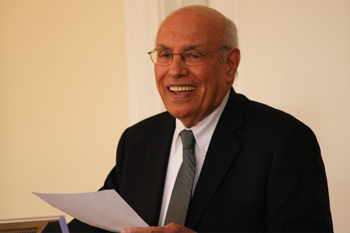

Throughout his diverse career as a diplomat for the United Nations, a law professor, and a practicing lawyer, Yassin El-Ayouty ’53 has never lost the connection to his teaching roots.

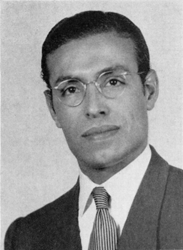

After more than five decades of intense engagement in world affairs, Yassin El-Ayouty ’53, PhD, still gives a vivid and humorous account of his arrival on the College’s campus in the early 1950s. After a 21-day journey by boat from Alexandria, he reached the United States with exactly $58.50 in his wallet. The leaders of the 1952 Egyptian Revolution who deposed King Farouk frowned on the exportation of hard currency, thus leaving the young El-Ayouty cash-strapped.

“I was actually hungry, but not Americanized enough to say so. Rosemary Hausdoerffer, the wife of Dr. William Hausdoerffer, [then] dean of men, gave me a wonderful glass of milk. Dr. Hausdoerffer then asked me if I had eaten and I told him that I had no money,” El-Ayouty recounted. “I’d spent about 10 cents for a bottle of Coca Cola over the previous 21 days on the ship from Alexandria.”

“And he said, ‘See that house over there—a retired faculty member needs help putting in storm windows.’ I’d never heard of those. We don’t have that kind of storm in the desert. But I went up and down from the basement 22 times and then sat down and talked to 12 ladies over coffee about the Egyptian Revolution. After 45 minutes each one raised a hand with an envelope, and I received $5 from each. I’d become Donald Trump!”

El-Ayouty’s accomplishments in the years that followed would prove even more significant on a global scale, yet he never forgot the College that he now calls his “first and everlasting alma mater in the U.S.”

When he arrived here more than 50 years ago, El-Ayouty was both an effervescent young teacher with an unusual pedagogical approach and a keen student as well, with a seemingly limitless capacity for new intellectual and cultural experiences. It was his singular teaching methods—relating modern Egyptian history through songs, plays, and field trips in his native country—that attracted the attention of U.S. education officials and won him a Fulbright scholarship to apply his creative techniques in New Jersey schools.

“I don’t believe in teaching just within walls,” he said in a recent interview. “While teaching about Napoleon’s invasion of Egypt, I took my class to Alexandria so they could see where Napoleon arrived. In teaching about the strategic importance of Egypt, I took them to the Suez Canal. We should always look, analyze, and involve the community when possible.”

It was his scholarly appetite that propelled him on a lifelong educational journey that began with teaching, and moved on to history, political science, and the theory and practice of law, earning him a bachelor’s and master’s degrees, a PhD, and a law degree along the way. Yet throughout the diverse career that followed—as a diplomat for the United Nations, a law professor, and a practicing lawyer—he never lost the connection to his teaching roots.

Now, 56 years after earning an undergraduate degree at the College in primary education, El-Ayouty is still engaged in the world as a teacher, traveling extensively with SUNSGLOW, an organization he founded a decade ago as a vehicle to help train judicial and legal communities in what he calls “emerging systems” in the developing world.

El-Ayouty and his team of advisers and young associates from around the world offer training programs that familiarize lawyers, judges, and other citizens with their countries’ existing laws and with ways to access them. They also introduce them to such emerging legal issues as frivolous and class-action-scale lawsuits and help them learn to navigate the increasingly complex arena of international law.

“There is the teaching of law as theory, and then there is training, which converts information into skills. I’m always after the new concept,” he added. “And what’s new in law today is that it has no boundaries. Economic and environmental issues, for example, cross borders and affect all kinds of disciplines.”

He is in the process of setting up a program that would address piracy in the ocean waters off East Africa by seeking to coordinate international criminal law and enforcement efforts among the many countries affected by it. The program would likely be based either in Saudi Arabia or Egypt, riparian states that overlook the Red Sea, which flows into the now-dangerous Gulf of Aden off Somalia, and would bring in representatives from countries whose navies patrol those seas, such as the Netherlands, the United States, Japan, India, and China.

“The income of the Suez Canal Authority has been decimated, reduced by 50 percent, as a result of this piracy,” said El-Ayouty, who called the headline-grabbing Somali plunderers “an old phenomenon, but new in their methods.”

“We would look to establish representatives from all of these countries, including academics, trade experts, and legal gurus to see in what ways SUNSGLOW could help develop a model action program to better protect trade,” he said. “International law is only one instrument here and we need to focus attention on how to deal with the matter. It is a crime and there is a need for better cooperation.”

The Manhattan-based SUNSGLOW, which has affiliate centers in eight other countries, grew out of El-Ayouty’s 32-year career at the United Nations, where he held positions ranging from chief of the Africa division, to secretary of the UN Council for Namibia, to director of training for the U.N. Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR).

“I spent seven years as director of training at the UN, taking junior diplomats from emerging systems and training them how to draft resolutions, negotiate, reach compromises, and serve their countries while also coordinating with others by learning to live beyond their flag. Training has always been part of me,” he says.

In 1999, then Secretary General Kofi Annan declared SUNSGLOW a partner organization with the UN. Its international board of advisers includes legal experts such as Mohamed El Baradei, director general of the UN’s International Atomic Energy Agency, and the Hon. Raymond Dearie, chief judge for the U.S. District Court, Eastern District of New York.

El-Ayouty is also a practicing lawyer, who takes cases that relate to his areas of expertise, including diplomatic immunity, international sanctions, immigration, national security, and international criminal law. He earned his law degree at the age of 66 after discovering that his PhD in international law from New York University did not by itself permit him to practice.

“I made an error,” he recalls. “I thought that I would be able to practice law, but that is not allowed. So I went back to law school and got my degree from the Benjamin N. Cardozo School of Law, which is part of Yeshiva University. I was the first Arab Muslim at a distinguished Jewish law school.”

Read about one of El-Ayouty’s cases that made headlines worldwide.

El-Ayouty has observed that political conflicts are rarely as simple as the media often depicts them. In 2006, he was named to a panel of experts on Darfur by the UN Secretary General. In his report on the conflict, “The Darfur Crisis: Legal, Political and Tribal Perspectives for the U.N. Security Council Committee on the Sudan,” he sought to portray the complexity of a political struggle that is not simply a clash between the Arab-led government and other African minority groups.

“It’s not just the government versus the people, or Arab versus African. Those are just aspects of the situation. There are also inter-tribal problems, with one tribe versus another, including Arab versus Arab. There is a conflict between farmers and pastoralists,” he said, “It is a churning cauldron and [Sudan President Omar Hassan] al-Bashir himself is only part of the problem.”

Looking back again to his arrival on campus, El-Ayouty remembered that after his successes as a storm-window installer, he quickly moved on to babysitting. His gifts as a storyteller earned him a loyal following among neighborhood children, and he joked that he was, “soon swimming in dollars.”

“My first story was about a big Indian chief—all fiction, constructive fiction—and then the whole neighborhood wanted me,” he said.

El-Ayouty—who published the novel Dajjal Fi Qaria (Witchcraft in the Village) in 1948—said the art of storytelling should never be discounted, particularly by historians and teachers.

“My father was a professor of Islamic history and philosophy, and I grew up in a history-laden home in the eastern part of Egypt, which is largely desert and somewhat remote. There was nothing like television there and so you ended up learning how to tell stories,” he said.

“To me, history is storytelling and that is very important. I hate deadly, boring things. We need to present information in such a way as to make it alive.”

Posted on August 12, 2009