Shattering Barriers and Opening Doors

TCNJ is leading the way in improving the lives of people with with a wide range of developmental disabilities—from autism spectrum disorder, to Down syndrome, to cerebral palsy—and in preparing teachers to work with these populations.

When Asim Safdar and Bridget Reilly ’09 met three years ago, both were new to the campus and pioneers in an innovative new program that pairs special education majors with nontraditional students.

When Asim Safdar and Bridget Reilly ’09 met three years ago, both were new to the campus and pioneers in an innovative new program that pairs special education majors with nontraditional students.

Safdar was, by his own admission, somewhat shy at first, and not at all eager to embrace new experiences.

“He was apprehensive about meeting new people and doing new things,” recalled Reilly, who is now pursuing a master’s degree in special education. “It was like pulling teeth to get him to try anything new.”

But skip ahead three years and the friend Reilly now describes is a far cry from that reticent freshman. He has developed a network of relationships on campus, become adept at absorbing material in class, and discovered, among other extracurricular pursuits, a passion for bowling.

“He’s a chatterbox. He seems to know everybody,” Reilly laughed.

Safdar is among the debut class of the now three-year-old Career & Community Studies (CCS) Program, a four-year certificate program for students with a wide range of developmental disabilities, from autism spectrum disorder, to Down syndrome, to cerebral palsy. He takes a mix of courses designed specifically for students in the program that focus on personal goals, vocational aptitudes, and health and wellness, among others, as well as classes that are open to everyone.

It is one of several new programs and courses at TCNJ that reflect new thinking about disabilities such as autism spectrum disorder, while shattering old barriers that often restricted capable students to vocational training. It dovetails with another recent offering at TCNJ, a five-year master’s program in special education that, among other forward-looking elements, taps students to serve as mentors and aides to students with disabilities.

Reilly, for example, worked alongside Safdar last semester in a nursing class on child development.

“Bridget took notes, because it’s easier for me to listen,” Safdar said. “I learn best by listening.”

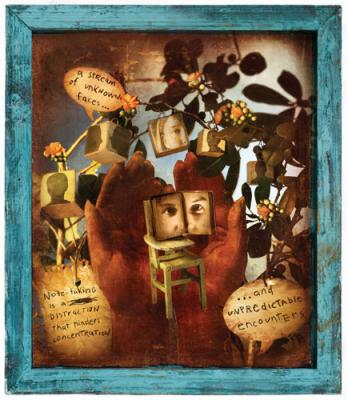

Reilly called note-taking a distraction that hinders concentration for many students with developmental disabilities, particularly for people with autism who struggle to process what seems to them at times like a sensory overload.

When Reilly helped Safdar prepare for the final exam in his nursing class by going over study guides she had prepared, she was impressed with his progress. She worked closely with him his freshman year and recalled their lengthy study sessions in those early days, and said she was recently struck by how many of the questions he could answer straight off, just from listening in class.

“He had developed great test-taking skills,” she noted.

The CCS program was founded on the belief that students with disabilities, given meaningful support as well as effective adaptations and reasonable accommodations, can participate successfully in post-secondary classes.

“The assumption is sometimes made that people with intellectual disabilities can’t learn, and that they’re not smart. I know from 25 years of experience that this is not true,” said Richard Blumberg, an assistant professor of special education, language, and literacy and one of the program’s founders. “So we decided to use the campus as a lab to explore what a program with rigorous liberal learning would look like for students with developmental disabilities. We don’t think we should just be preparing these students for jobs, but helping to connect them with their communities.”

He said a liberal education should look and sound much like it does for so-called neurotypical students. As the rest of their peers do, the CCS students strive to become effective speakers and writers, to use technology competently to communicate, and to become fully participating citizens in a global world.

He said a liberal education should look and sound much like it does for so-called neurotypical students. As the rest of their peers do, the CCS students strive to become effective speakers and writers, to use technology competently to communicate, and to become fully participating citizens in a global world.

“Students with [intellectual disabilities] are capable of achieving those goals. They may make some modifications in the process of getting there, but the goal is the same,” Blumberg said, adding, “What they’ve been missing is being a part of the larger cultural conversations.”

In addition to their courses, students in the program also serve in internships on- and off-campus in jobs that reflect their career interests. Safdar, for example, has worked in administrative offices on campus and at the College gym, and off-campus for the Educational Testing Service. To prepare for job interviews after they receive their certificates, they compile electronic portfolios of their projects.

He and five fellow students will be the first CCS graduates to earn certificates next spring and their progress has attracted notice here and abroad. Blumberg and Rebecca Daley, a program coordinator in the School of Education and a CCS co-founder, presented their findings on the program at an International Association for Special Education conference held in Spain this summer.

As defined by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, autism spectrum disorders are a group of developmental disabilities that include impairments in social interaction and communication and the presence of unusual behaviors and interests. The agency notes that people with autism often possess unusual ways of learning, paying attention, and reacting to various sensations.

It was just over 50 years ago that Leo Kanner of Johns Hopkins University first applied the term autism to a group of socially withdrawn children. For many years after, the disorder was incorrectly associated with schizophrenia.

“The causes of autism have puzzled since its inception, from thoughts that it was the result of cold and unattached mothers to the result of preservatives used in vaccinations,” said Jerry Petroff ’75, an associate professor of special education, language, and literacy and CCS co-founder.

And it was not until 1975 that the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act promised these students a free and developmentally appropriate education. Until fairly recently, however, they were often segregated.

In 2007, New Jersey Governor Jon Corzine signed a package of bills that provided funds to help train teachers to work with students with autism spectrum disorders, including Asperger syndrome and pervasive developmental disorder, and other developmental disabilities, and for early intervention in identifying and treating children with autism and for research and treatment, among other areas.

“There has been a huge push in New Jersey to have kids in the least restrictive environment and this pushed public schools to improve their services,” said James Ball ’84, MA ’89, the president and CEO of JB Autism Consulting. Ball, a New Jersey-based behavior analyst who works with organizations, schools and families on training, home support services, classroom design and behavior management, is one of the country’s leading advocates for adults with autism. He noted that the Corzine administration provided much needed funding to help teachers and districts design curricula.

Federal lawmakers have also passed several recent bills that provide money for research and educational and community support. U.S. Rep. Chris Smith ’75 is the co-sponsor of a new bill, the Autism Treatment Acceleration Act of 2009, which would establish model care centers to improve and coordinate care for people with the disability and require health insurance companies to cover its diagnosis and treatment.

“The battle against autism requires an ongoing commitment to adequate funding for research and public awareness, and it also demands innovation,” Smith said in a release. “This bill explores new ways to treat autistic patients, to train health professionals and to educate the public about this widespread, yet little understood developmental disorder.”

“It was a perfect storm, with all of these things aligned, and [TCNJ] needed to respond—and we did,” said Petroff. He noted the number of new courses on campus that focus on these disabilities and the new five-year special education program, which requires students to prepare to teach students with significant developmental disabilities, and to learn constructive approaches to approach behavioral problems.

Petroff believes it is important to prepare teachers to meet the needs of these students in mainstream classes whenever possible. “I teach an entire course on inclusive practices—how do we arrange to reach the widest audience as well as the individual,” Petroff said. His classes may include multilevel and overlapping curricula and the use of assistive technology to level the playing ground. So-called augmentative devices that aid in communication include picture boards, computers, and sign language.

Petroff noted that the field of special education struggles to meet the mandate of educating students with disabilities within the least restrictive environment. Including these students in a general education setting is now thought to be the placement of first choice, a belief “rooted in the similar sensibilities as presented through the Brown vs. Board of Education decision, where separate may not be equal,” as he put it.

Perspectives on autism have changed dramatically in recent years as scientists and educators better understand its neurological basis and the effect on behavior and development.

“We now see it as a movement difference that is typically manifested in difficulties with starting, stopping, and switching actions,” said Shridevi Rao, associate professor of special education, language, and literacy. It can make opening a car window a laborious procedure.

A clearer understanding of intellectual disabilities and their impact on the learning process has enabled educators to provide supports and accommodations that allow students to succeed in their classes.

“The idea used to be that you had a disorder and professionals fixed you. But now it’s more about creating a supportive environment, about how we change the world to make it work for you,” said Blumberg, adding, “We’re finding that a lot of young people with autism spectrum disorders can be successful college students with some supports.”

He noted that accommodations can be as simple as letting an overloaded student take a break from class by strolling down the corridor to get a drink. Some improvements, such as better lighting and quieter classrooms, help the entire student population, he and colleagues say.

He noted that accommodations can be as simple as letting an overloaded student take a break from class by strolling down the corridor to get a drink. Some improvements, such as better lighting and quieter classrooms, help the entire student population, he and colleagues say.

Another way that TCNJ professors try to build understanding for autistic students is to encourage future teachers to see the world through their eyes.

Rao teaches a freshman seminar that looks at autism from the perspective of people who live with it, such as author Temple Grandin.

“The posture our students take with students with disabilities, and especially autism, is to challenge the more traditional lens through which autism has been viewed—to try to appreciate the vantage point from being on the spectrum and to focus on the individual, not the label,” said Rao.

One of Blumberg’s assignments is the virtual student project. He gives his students a profile of a student having difficulties at home and school, and asks them to come up with a profile that includes the student’s home life and peer relationships, among other features, and to assess the student’s abilities and challenges, while designing social and academic intervention and supports.

Students are also required to spend a significant amount of time outside of the classroom in work settings. In addition to serving as a peer mentor, Reilly, for example, has had several field placements in special education settings to complement her classes.

“To be a special education teacher is to be no ordinary teacher. It’s very important that you have your heart in it, and people need to have classroom experience, as early as freshman year, to see if their heart really is in it,” she said.

After earning her master’s degree, she is looking forward to working with some of the most severely disabled students and will advocate mainstream settings for them whenever possible.

“I hope that my generation will spread its positive attitude about inclusion to the non-believers,” Reilly said. “It’s beneficial for everyone, including the students without intellectual disabilities, who get the chance to learn about differences, tolerance and equal opportunity.”

Click here to read about autism research advocates with ties to TCNJ.

Posted on August 17, 2009