Powerball

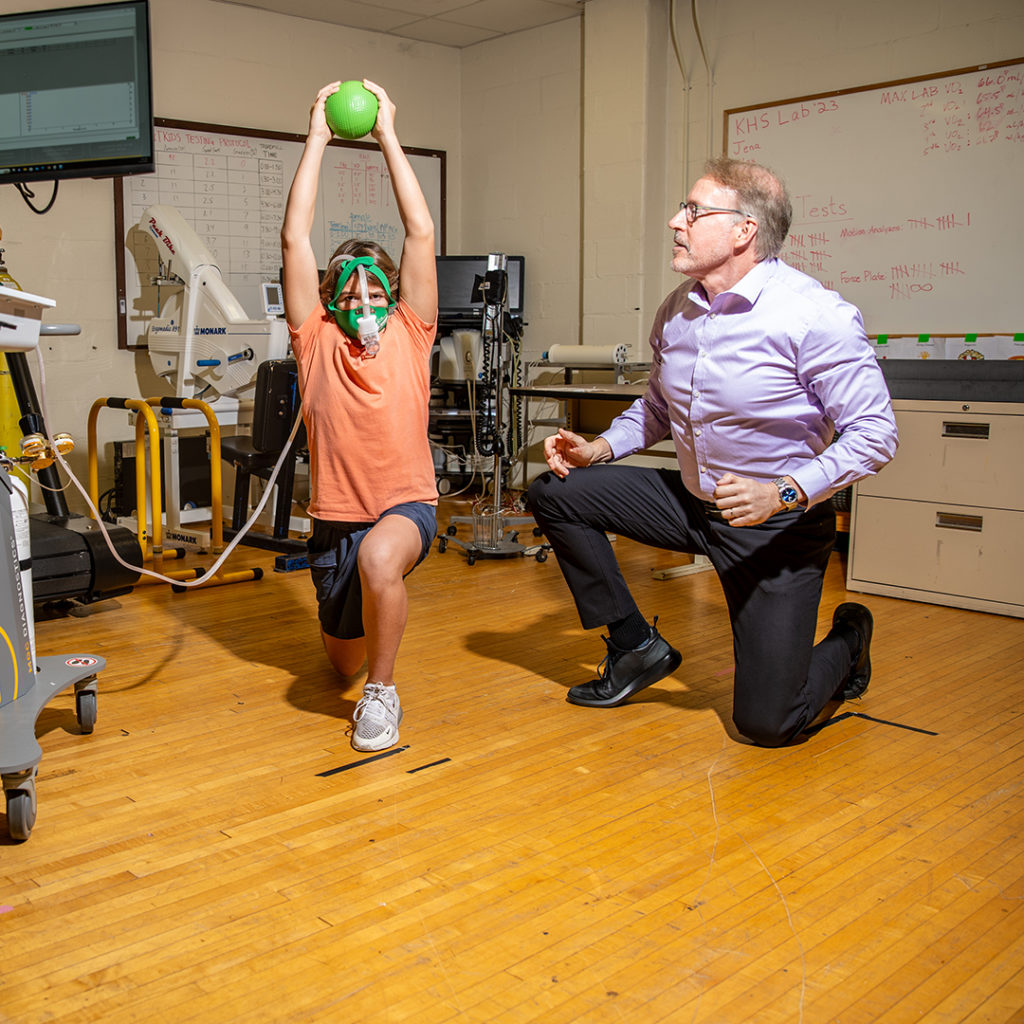

Avery Faigenbaum shows his strength as a pediatric exercise researcher and policy changer.

Avery Faigenbaum

About a dozen years ago, Avery Faigenbaum hopped in his car and hit the road, on a mission to glimpse his life’s work in action.

His excitement stemmed from an email he’d received from Mike Bukowsky, an elementary school physical education teacher in North Jersey. Bukowsky had created a fitness circuit for his fifth graders, guided by Faigenbaum’s research about the importance of strength-building exercises for children. He thought he’d share a short video, in case Faigenbaum was interested.

He certainly was.

Soon, Faigenbaum was in Westfield, watching the young students arrive for class. There was no hesitation, no dawdling at the door; instead, they flocked to Bukowsky as he tipped a trash can of medicine balls onto the floor.

“They pick up the medicine balls, and then they’re moving, moving, moving,” Faigenbaum says. “I’m like, ‘Wow. He did it.’”

Strength training typically conjured images of bodybuilders, not elementary school students. But Faigenbaum, now celebrating his 20th year as a professor of health and exercise science at TCNJ, refuted the long-held idea that strength-building exercises would harm growing children. In fact, his early research had established just the opposite: such training not only increases muscular fitness and fundamental movement skills in children, but can also improve cardiometabolic health, help manage weight, and increase bone mineral density. In obese children, he discovered that the training could be even more transformational, critically boosting confidence alongside physical gains.

As Faigenbaum’s studies challenging the myths about the dangers of strength-building activities gained speed, invitations to share his findings began to arrive from scholars around the world. And, the exuberant scene in the gymnasium demonstrated that, most importantly, the science was beginning to reach teachers on the ground.

“It was a slow burn of a journey,” he says.

Today, Faigenbaum’s decades-long quest to spotlight the importance of strength training has reshaped the field of pediatric exercise science. “A prerequisite level of muscle strength is needed to move at any age,” says Faigenbaum. With strength training, children can use their own body weight as well as medicine balls, dumbbells, and elastic bands. “This type of exercise provides a nice balance between skill and challenge,” he says. “As they see themselves get stronger they gain competence and confidence in their physical abilities and, consequently, are more likely to engage in sport activities.”

Desultory games of dodgeball and halfhearted laps around the gym are steadily disappearing as kids hoist small medicine balls, train with heavy ropes, and giddily crab walk with balloons on their stomachs in schools around the world.

Faigenbaum’s work — once considered controversial — has been cited more than 26,000 times to date, its findings prompting leading health and medical organizations, including the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Academy of Pediatrics, to update child fitness guidelines to include strength training. The International Olympic Committee has even tapped him to consult on its recommendations for youth athletic development.

“He is pretty much the main source of pediatric exercise science,” Bukowsky says. “He is the guru. I call him the GOAT, the greatest of all time.”

Faigenbaum remains fueled by a sense of urgency over what he describes as “a vortex of inactivity” in the United States, where less than a third of children between 6 and 17 years of age meet the recommended guidelines of 60 minutes of physical activity per day.

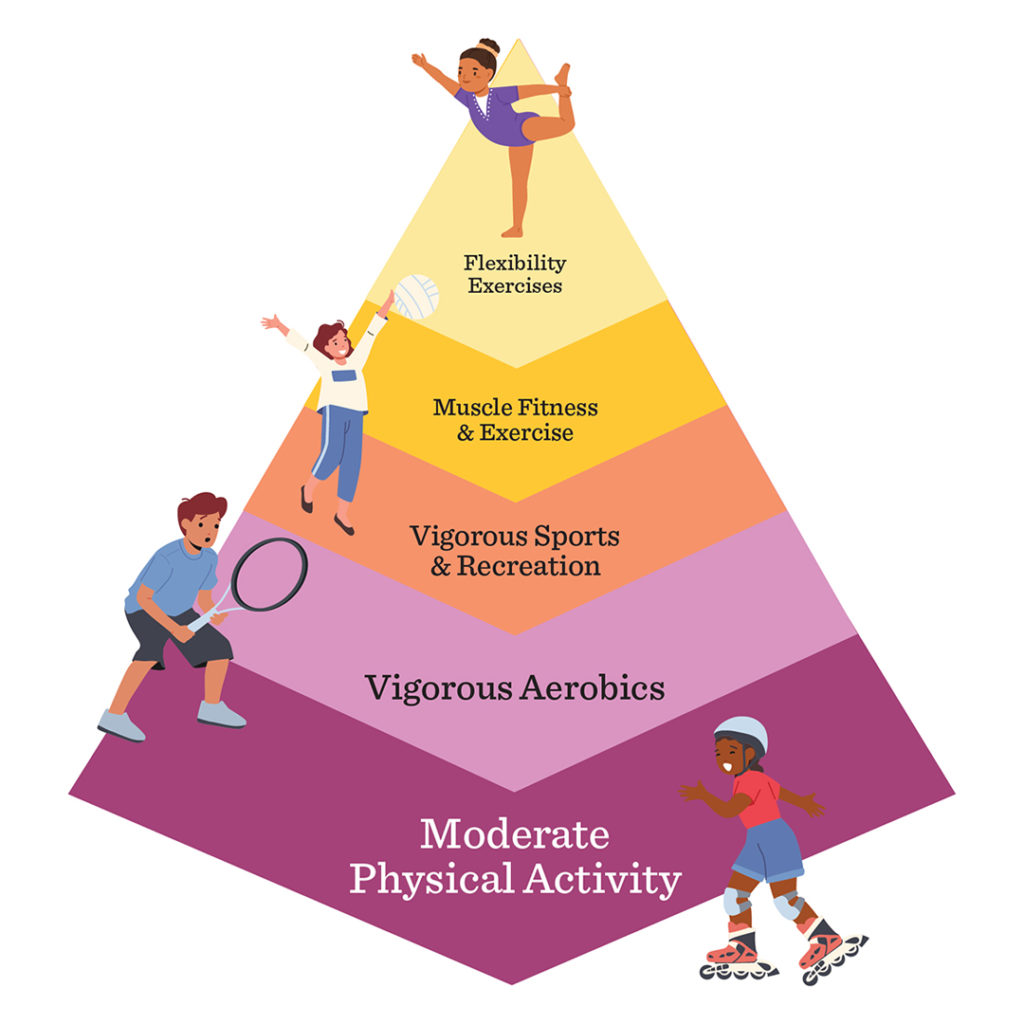

These days, he is leveraging his research to push for policy changes. Since 2020, he has twice won the ACSM’s prestigious paper of the year award; one paper highlighted the impact youth fitness programs can have on mental health, while the other delved into an emerging passion, his efforts to overhaul the physical activity pyramid that serves as a guide to health and wellness recommendations for kids.

The current pyramid prioritizes aerobic activity as its base and relegates strength training to twice a week; Faigenbaum argues that updating the pyramid to make strength training as foundational as aerobic activity will help children acquire the skills they need to embrace physical activity — and the sooner they start, the better.

“Once they get to first grade, we engineer physical activity right out of their life,” Faigenbaum says. “I often tell folks that if we wait until high school to intervene we are 10 years too late.”

Faigenbaum’s early years in the field were not easy, but he hadn’t expected them to be. When he decided to focus his doctoral research at Boston University on youth strength training, his advisor, sports scientist Len Zaichkowsky, warned him there’d be pushback; the idea that young children might need to increase their muscular fitness was taboo.

But Faigenbaum decided to let the science, not the skeptics, lead the way.

He assembled a research team made up of Zaichkowsky and a handful of colleagues in Boston interested in challenging the conventional wisdom on the topic. The group included Lyle Micheli, then the director of sports medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, and Wayne Westcott, a strength-training expert and fitness director at a local YMCA. Their first study tracked the effects of a twice-weekly strength-training program on boys and girls between the ages of 8 and 12.

“Surprise, surprise, the children got stronger,” Faigenbaum says. “There were no injuries. The children enjoyed the program. And we started to improve some motor performance skills, like their ability to jump and run.”

He produced dozens of papers expanding the field’s understanding of youth strength training, with studies tackling topics ranging from its psychosocial benefits to how it could reduce sports injuries in young athletes. In particular, his work documented how strength training gave overweight children, frustrated by aerobic activity, an opportunity to be successful and provided a gateway to increased physical activity.

After joining TCNJ in 2004, Faigenbaum’s reputation among teachers and scholars alike continued to grow. When Carole Kenner became dean of TCNJ’s School of Nursing and Health Sciences in 2014, she immediately asked Faigenbaum to work on a community program, funded with a $50,000 grant from Novo Nordisk, aimed at improving nutrition and conditioning in kids.

“He’s always believed that there has to be a combination of the academic/theoretical and then the application, and the application also has to have a component in the community,” she says. “Very few people in exercise science really put that together, especially in terms of pediatrics and wellness.”

Faigenbaum’s impact on his field has been amplified by not only the scope of his work, but its reach. He’s pushed to get the research into the world, accepting invitations to share his research with police departments, fitness councils, sports camps, rehabilitation centers, hospitals, schools, and colleges and universities throughout America and as far away as Argentina and Australia.

His speeches carry titles — “May the Force be with Youth” and “From iPod to iPosture” — meant to engage listeners, while his papers reject the stiff jargon found in some academic writing. A recent article that went viral warns readers that the negative “mythology of youth resistance training remains a zombie tale that will not die.”

Such efforts at inclusion and outreach are no accident. “Half my work is research, and half is changing practice,” Faigenbaum says, adding “We have to bridge the gap from the lab to the playing field.”

Faigenbaum’s generosity with his time and scholarship, whether sharing studies on bone density or teaching colleagues in underserved schools how to build a medicine ball out of old soccer balls, sets him apart.

“It’s unique for a researcher to not only be able to do the research, but to connect to the people that it will impact,” says Andrea Stracciolini, director of medical sports medicine at Boston Children’s Hospital, who is a longtime collaborator of Faigenbaum’s.

Faigenbaum’s work with overweight children inspired Stracciolini to seek him out when she was a young doctor and ask to shadow him in his lab at TCNJ. There, observing how he engaged the children and studying his rigorous approach to research, Stracciolini resolved to help him shrink the disconnect between clinical pediatric care and exercise science research.

“I thought to myself, ‘This guy holds the key to child health,’” she says. “He was a visionary. How many people can say ‘I can take kids who are physically inactive, that are obese and aren’t interested in exercise, and I can empower them. I can give them confidence.’ Not many.”

Faigenbaum is gratified to see a new generation of researchers embracing and building on his scholarship, but sometimes can’t quite believe the extent of it all. When he recently learned that a doctor in Australia planned to prescribe strength training for pediatric cancer patients in remission based on his research, he was both stunned and thrilled.

“If you said to me in 1990, ‘Well, in 30 years your work will reach the point where clinicians are now going to prescribe this for children who are cancer survivors,’” he says, “get out of here.”

Yet, Faigenbaum worries there is still much work to be done.

“We have a generation who are turned off to physical activity,” he says. “What we need now are targeted interventions that recognize the foundational level origins of muscle strength and motor skills early in life.”

If the first half of his career drove change one paper, one teacher, one school at a time, Faigenbaum hopes the second half prompts widespread policy changes.

Along with pushing for a new fitness pyramid, Faigenbaum is also advocating for an increase in physical education classes in school and for pediatricians to integrate comprehensive physical activity markers into childhood wellness checks. He is developing a new youth fitness certification for the American College of Sports Medicine that he hopes will provide a basic understanding of pediatric exercise science for teachers, coaches, and youth fitness instructors.

And, as ever, he is at work in the lab.

“Did I make an impact?” he says. “I think I did. But I’m not done yet. I’m just warming up.”

Pictures Bill Cardoni

Posted on February 4, 2024