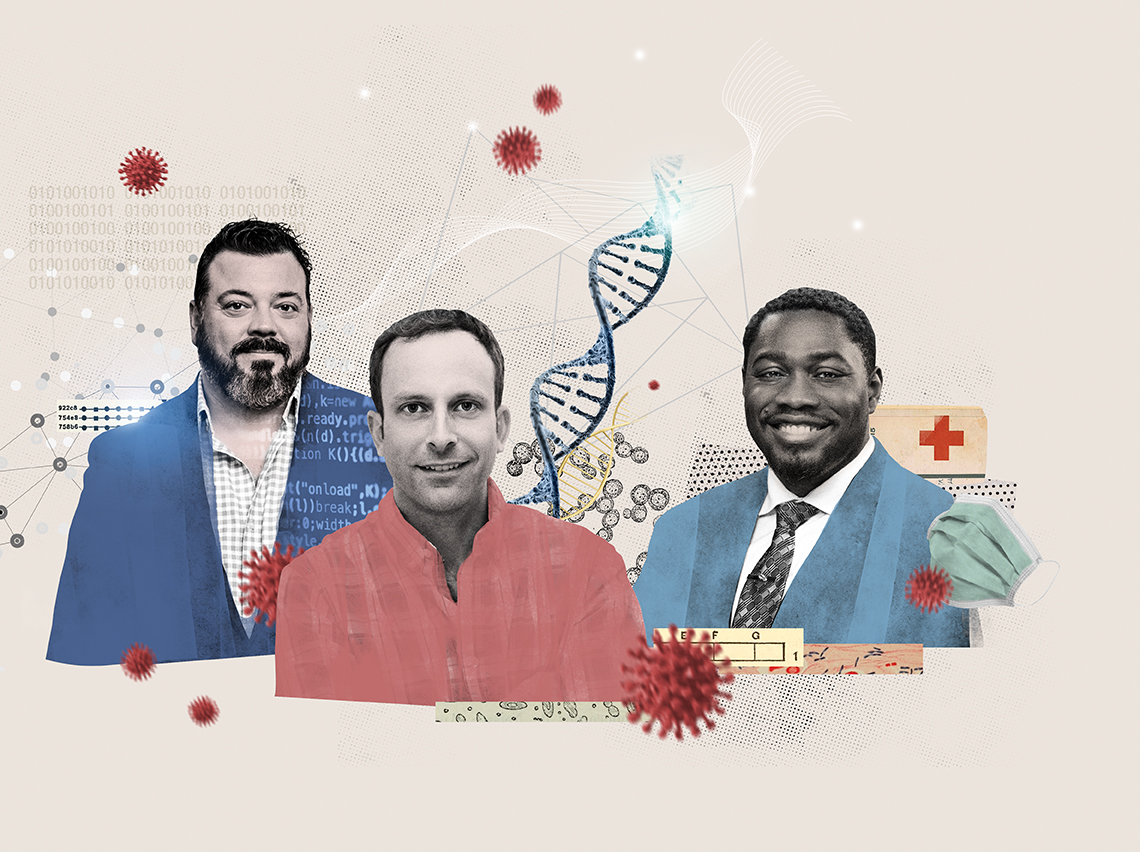

Crisis innovation

When COVID-19 took hold, our world changed. So, too, did the operations of every industry. Here’s how three alumni embraced the challenges and brought bright ideas to dark times.

When COVID-19 took hold, our world changed. So, too, did the operations of every industry. Here’s how three alumni embraced the challenges and brought bright ideas to dark times.

Frank DePierro ’03 collects vaccine data at record speed.

When coverage of the pandemic took over the media in the spring of 2020, Moderna and Johnson & Johnson were the first companies to announce they were making a COVID-19 vaccine. Those names quickly became synonymous with what was hoped would allow us to live with some normality again. Visits with Grandma and Grandpa. Evenings out in our favorite restaurant. Even routine trips to the grocery store.

The team at Pfizer, including senior director Frank DePierro, wondered why their company wasn’t in the COVID-19 vaccine game, too. After all, Pfizer had a strong vaccine portfolio, brilliant scientists, and thanks to DePierro, a strong informatics team that he had built from nearly scratch in his 15 years with the pharmaceutical company (11 of which were in vaccine research and development).

The world was waiting, and when the decision finally came down from management that Pfizer would begin development of a vaccine, it became top priority. “It went from nothing, to ‘This needs to move really quickly,’” says DePierro. A lot of pressure was directed at the scientists and the labs, but as they worked, they turned to DePierro’s team to provide information systems for the data and analytics to tell them if the science was sound.

That urgency meant that DePierro had to rethink standard operations without sacrificing safety, quality, and science. In normal times, his team supports Pfizer studies with computational systems and models that provide necessary data — data that regulators require and helps scientists to decide when to toss an idea, when to push it, and when to take that next step.

But with COVID, the serial steps that would normally take place in the labs — for example, allowing sample processing, determining formulations or dosage, and how to analyze data — had to be thought through all at once. The science behind the vaccine couldn’t be rushed or changed, so the time had to be made up in the collection and analyzation of the data. “My team programmed systems for all these various outcomes and performed statistical analysis of all these things in parallel,” says DePierro.

“We were starting to build systems when we didn’t even know what was going to be needed yet,” he says. Having the systems in place meant the scientists could receive and process hundreds of thousands of clinical samples, and move forward on ideas that showed promise. The quest became 24/7 for months on end.

In late 2020, as the world learned that Pfizer had produced a vaccine to combat COVID-19, the excitement was building inside the walls of Pfizer’s labs. But so were the nerves of DePierro and his team. Everyone knew that they finally had enough data to determine effectiveness. They just didn’t know how effective the vaccine might prove to be. “No one knew that the data was going to come back at 95% effective at preventing COVID-19,” says DePierro. “It could have just as easily said 35%.”

While other vaccine manufacturers shared efficacy results soon after, in this case, it wasn’t all about competition. It was about creating a solution to a worldwide problem in record time.

As he watched people in line for COVID vaccines as 2020 wound down, all those hours and forethought paid off. “Wow,” he recalls thinking. “My team helped make that happen.”

Greg Porreca ’02 isolates pockets of genes to find virus variants.

When Greg Porreca was earning his PhD, he worked in a lab with an entrepreneurial advisor. Together they took many projects — focused on genetic testing — right from lab to industry. “From that point, I got pretty excited about working in industry versus being an academic scientist,” he says.

Porreca quickly made a name for himself in business, co-founding a company that would provide genetic testing for in vitro fertilization patients. When the company was acquired, he took the knowledge he had gained from the experience and developed another company, Molecular Loop, a group that provides kits that allow labs to do genetic testing around issues like reproductivity and inherited cancer.

The broad technology behind the business is DNA sequencing — reading the gene sequence of a patient or a virus. But typically, labs don’t need to see the whole genome sequence to do their work, just specific areas, which scientists can isolate by using specific reagents or compounds. “Our kit allows the laboratory to isolate just the regions that they’re interested in,” says Porreca. “So, if we’re working with a lab that’s doing inherited cancer, we would sell them a kit that has the reagents that they need to isolate the cancer genes. Or if it’s a lab that’s doing reproductive testing, there would be a different set of reagents in there to isolate out the genes that are relevant to that.”

Molecular Loop was doing good business, but then the pandemic disrupted their progress. Suddenly every one of his lab clients were focused on COVID testing. “We said, ‘You know what? We think we can adapt our technology to do variant monitoring,’” says Porreca.

Molecular Loop spent the better part of 2020 rethinking their technology to help in the fight against COVID-19. By early 2021, they were ready to shop their COVID testing kits around to a few big labs, including Labcorp, a major player in the testing scene. “Over a period of a few months, we fine-tuned it with them,” says Porreca. “They decided that all of the variant monitoring work they were doing for the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention would be done using our kits.”

Molecular Loop’s kits allow labs to determine whether or not a patient has COVID, and can also determine if a positive COVID sample contains a variant — ultra important info for the CDC to have in hand as new variants like Delta and Omicron make their way across the world. “All of these sequences get sent to the CDC so that they’re able to see in a community whether new things start circulating,” Porreca says. It also helps the CDC determine exactly how much of each variant strain is out there.

Molecular Loop’s kits are not the only products on the table, but they tend to be simple to use and offer a wider look at the COVID landscape.

“Our solution allows scientists to see more of that full genome than they can see with other technologies. That translates into more data for the CDC and a higher chance that they’re going to pick up a variant,” says Porreca.

As we learn to operate in a new world, Molecular Loop will add their COVID kits to their other line of products and broaden their portfolio and build a bigger team. Says Porreca, “It’s all in how you react to a situation and turn it into something that’s both good for business and good for society.”

Tosan Boyo ’07 cradles his city and gives room to grieve.

In early 2020, the San Francisco mayor’s office reached out to Tosan Boyo with a request that he help combat an impending pandemic as deputy commander of the San Francisco COVID-19 Operations Center, which was then working to track and quarantine travelers from China. But Boyo turned them down. As the chief operating officer of San Francisco General Hospital, the city’s only Level I trauma center and psych hospital, he had his hands full. So the mayor’s office sent a second request. Then a third.

Finally, Boyo offered to take on the position for a few weeks until he could make a recommendation for a new leader. But just as he was nearing his self-imposed deadline, the Grand Princess cruise ship arrived in the San Francisco Bay with 21 initial positive cases of COVID-19 on board. From that moment, the city’s work would no longer focus on returning travelers from China, and Boyo would, instead, spend the next nine months managing healthcare operations of COVID-19 for the city. It was a massive task. The city had to quickly create the infrastructure to manage the surge and coordinate among the Department of Public Health, and the Department of Public Safety, and the Chambers of Commerce. Ultimately, the work was a success. “One of the greatest accomplishments of my life is the fact that San Francisco had the lowest death rates and new case rates, and highest testing rates compared to any other densely populated city in the U.S.,” says Boyo.

By the fall of 2020, Boyo brought his experience battling COVID with him to another new position as senior vice president for hospital operations at John Muir Health. Now well into the pandemic, the city was about to enter its third surge of cases as the holidays crept close. Boyo was tasked with managing all operations of a hospital full of exhausted healthcare workers who had faced both the pandemic and the social unrest that followed the killing of George Floyd. In addition, Boyo was asked to lead the COVID-19 Command Center at JMH, which meant organizing vaccinations for his workers (some of the first in the U.S. to receive them) and for local communities — especially ensuring that the hardest-hit populations had equal access to testing and vaccines.

It was a complicated operation, but Boyo found that not all innovations through crisis have to be complicated. One in particular was beautiful in its simplicity: a space within JMH for healthcare workers to cry if they needed to, to process lost patients and family members and people like Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd. “As a leader, I asked myself: how do I stop the bleeding of my team who are feeling emotionally and physically drained?” says Boyo. “The answer was to acknowledge their pain and create a space to grieve.”

Though Boyo’s work is always supported by data, he refuses to lose the human element behind those numbers in both the populations he serves and in the staff that supports him in the work. “I feel like I discovered my life’s meaning when I discovered public health,” says Boyo.

“Because, for me, making an impact on a population became sacred. Every policy I’ve ever implemented or deployed, every clinic or hospital I’ve ever run, I’ve tried to improve access and support the population being served,” he says. “These are people with lives and jobs and families. They have never been numbers to me.

Illustration: Nazario Graziano

Posted on February 7, 2022