Destination: space

Look up — from helicopters hovering over Mars to tourism planned for the moon to sunshields the size of tennis courts — there’s a lot going on out there.

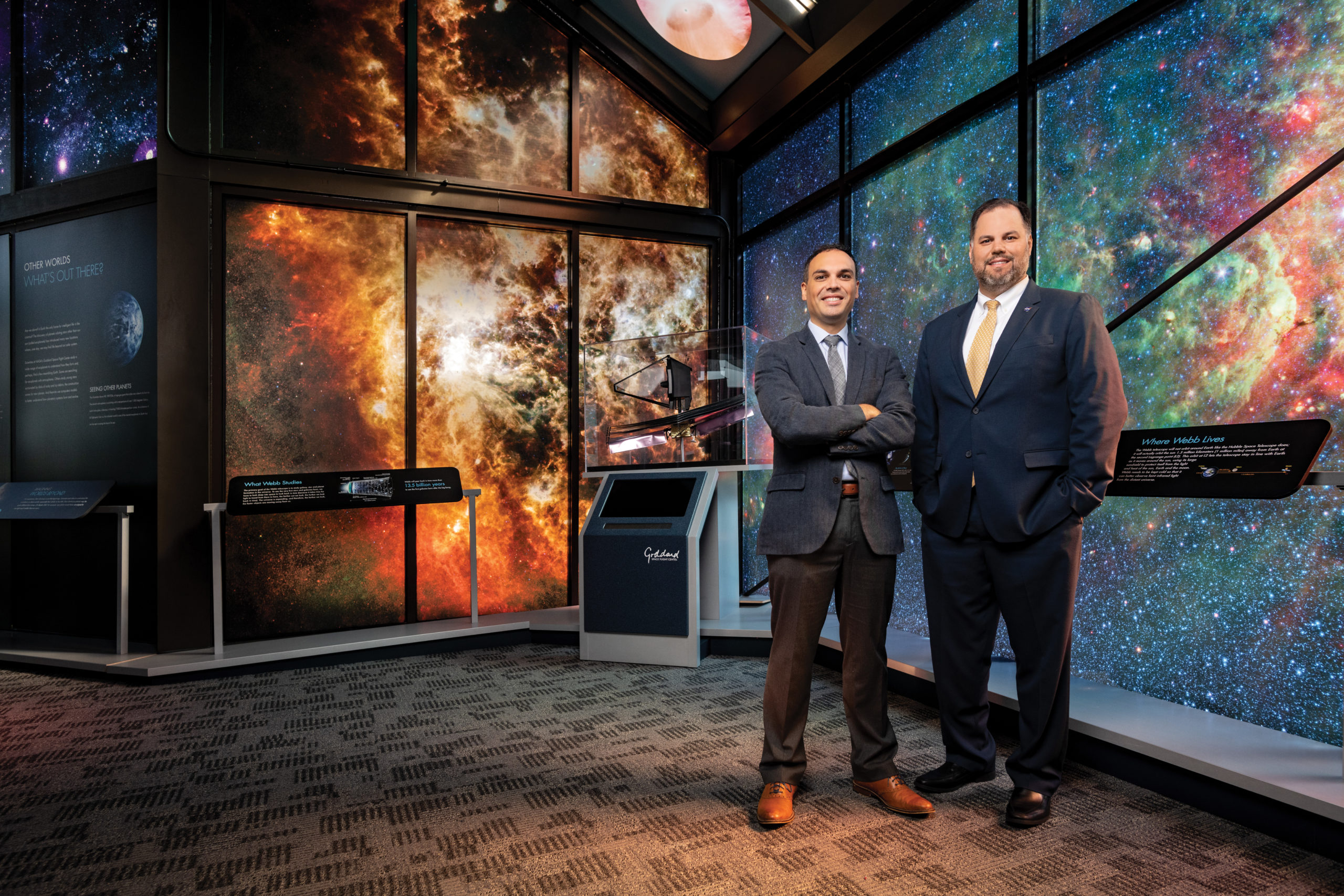

Kevin Gilligan and Steve Shinn, photographed at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt MD, 10 September 2021 for the College of New Jersey.

The final launch of the space shuttle Atlantis began with a burst of smoke and fire that shook the nearby earth. Kevin Gilligan ’09 felt the engines’ vibrations rumbling inside his chest as he stood, astonished, three miles away on an observation deck at Kennedy Space Center. It was July 8, 2011. Gilligan, who’d worked at NASA for less than a year, was witnessing one of humankind’s most extraordinary achievements, but his joy was tempered by the occasion itself.

“It was exhilarating,” he says. “But at the same time, it felt, from a human exploration perspective, like it truly was the end of an era. We were retiring the space shuttle. We were losing the ability to launch American astronauts, in American-made vehicles, from American soil.”

For years afterward, as Gilligan built a career supporting planetary-science missions that focused on advancing our understanding of the solar system, he fielded more than a few skeptical questions from strangers about NASA’s purpose.

“If I mentioned where I was working, people said, ‘Oh, I thought NASA wasn’t doing anything,’” he says. “I don’t get those comments anymore.”

A decade after the last flight of Atlantis — what many feared signaled the end of NASA’s fabled story — the pursuits of the reinvigorated space agency are once again mesmerizing the world. From hunting for life on Mars and plotting a spin around one of Jupiter’s moons, to building the world’s most powerful rocket to carry astronauts far beyond Earth, space exploration is in the midst of its most exciting stretch in a generation.

And Gilligan once again finds himself amazed at what is possible as NASA navigates this potentially historic new era. Now a senior program analyst in the Strategic Investments Division, Gilligan and his boss, fellow alumnus and NASA Deputy Chief Financial Officer Stephen Shinn ’97, are steering the financial operations and strategic-planning process of the agency’s highest-profile projects.

Many are mind-bending blockbusters that could, on their own, inspire entire sci-fi epics: the James Webb Space Telescope, a technological marvel that will allow astronomers to peer farther back in time than ever before toward the origins of the universe; the Perseverance rover, which successfully traveled nearly 300 million miles from Earth and now seeks rock samples on the surface of Mars in a search for ancient microbial life; and the Orion spacecraft, a deep-space vehicle whose heat shield measures a whopping 16.5 feet in diameter and will protect astronauts from 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit temperatures.

The Orion is a key piece of the agency’s mission to return to the moon, an ambitious plan, aptly named Artemis (after the goddess of the moon and twin sister of the Greek god Apollo), that will dominate the next decade. The effort casts a modern spin on NASA’s own mythology and storied past — beginning with a commitment to soon send the first female astronaut and the first astronaut of color to the moon.

“The next 10 years will redefine NASA,” Gilligan says. “I’ve seen the space vehicles and satellites and the people creating them all, and it hits you differently when it’s real. It’s not real for everyone yet, but when we launch astronauts to the moon again, and there’s true, live HD video of these folks approaching the moon, it’s going to be amazing. People will see NASA, and hopefully themselves, differently.”

And the moon is just the beginning: Artemis, which includes the construction of a lunar base and orbiting outpost, will serve as a bridge for future missions to Mars. By first successfully sustaining a long-term presence on the moon, NASA can develop the human habitats, tools, and technologies needed to support life in deep space — and embark on a new era of discovery and innovation.

The current sense of momentum is undeniable, but it didn’t simply emerge from the ether. Though the end of the shuttle program temporarily dimmed the agency’s public profile, its work continued.

NASA scientists and engineers pursued advanced nuclear rocket technologies capable of propelling next-generation vehicles to Mars, and the complicated instruments and design needed for the James Webb Space Telescope.

Meanwhile, the commercial space industry steadily grew, filling a hole the shuttle had left behind. SpaceX, founded in 2002 by entrepreneur Elon Musk, delivered its first cargo load to the International Space Station in 2012. Later technical innovations by companies like SpaceX and Blue Origin — founded in 2000 by Amazon’s Jeff Bezos — began to change the nature of spaceflight with the use of reusable rockets that dramatically lowered launch costs.

Suddenly, space tourism seemed less far-fetched. In 2017, then-President Donald Trump issued a directive instructing NASA to return astronauts to the moon and begin building a foundation for a mission to Mars. The deadline for the first landing? 2024.

The result is a perfect storm of scientific achievements decades in the making, finally coming to fruition on an accelerated scale. Shinn, who joined NASA in 2011 and became deputy CFO in 2016, describes the current moment as pivotal for both the agency and space exploration.

“We’re coming up with viable plans to land on the moon and sustain a presence there,” he says. “It’s not like we’re talking about 2040. We’re talking about the first woman and first person of color on the lunar surface in the very near future.”

Space fans by the millions are already paying attention; how could they not be? A flurry of space-centric events has filled the nightly news: Billionaires race to beat one another into space on private rockets. Satellites reveal July temperatures to be the hottest ever on record for the planet. A spacecraft’s research mission about an asteroid the size of the Empire State Building helps NASA scientists game the odds — 1 in 1,750 — of its hitting Earth.

In an era where life is endlessly chronicled on social media, it’s easier than ever to follow along on the journey. Sofia Stepanoff ’22, a double major in mathematics and physics who plans to pursue a career in observational astronomy, fills her Instagram feed with space news and watches SpaceX launches on its YouTube channel. The potential for widespread human spaceflight intrigues her less than its role in increasing scientific missions.

“Space tourism will fuel — pun intended — more exploration because it will make it cheaper,” she says. “That’s the part I’m excited about. It will make it easier to go to space.”

As a space operator for the U.S. Air Force in the 1990s, Lisa Loucks ’87 witnessed the fledgling days of the commercial space industry — and believed so strongly in its potential that she joined Sea Launch, a multinational company led by Boeing that launched the first satellite into space from the sea rather than land.

These days, millions of others share Loucks’ excitement for the growing intersection between NASA and commercial space companies.

“Shuttle launches became sort of yawners to some people because they happened so often,” she says. “Now, all of the energy from the newness of it is there for the commercial side, as well as all of the excitement for people who were tracking the NASA launches.”

The president of Ascendant Spaceflight Services, Loucks consults with commercial space companies on developing infrastructure and navigating federal regulations. The stakes for commercial spaceflight, she says, are much greater than simply letting the richest men on the planet travel to space.

“I think we’re at the precipice,” she says. “People might think it seems indulgent that we’ve got billionaires doing this space tourism, but if you think about it, it’s really practice.” Consider, she says, the aviation industry: at first, it was only the rich who flew on airplanes.

“Now everybody flies,” she says. “Think about that in terms of spaceflight, and not just from the standpoint of aspirational space travel. With things like the latest climate report, it might eventually become imperative for humanity and not a luxury. I think all that’s being done now is part of a vision for a future that may extend beyond Earth.”

The return of spaceflight could also expand research opportunities for astronomers like Lauranne Lanz, a professor of physics who studies the formation of galaxies. Once a presence on the moon is established, the scientific possibilities multiply, she says.

“How can we use that base as a jumping point to then go to Mars?” she says. “How can we use that to benefit astronomical research? How can we use that to develop technologies that will be useful back on Earth?”

NASA’s recent decision to fund research for the potential construction of a radio telescope on the far side is one example. The telescope’s position on the moon would allow astronomers to study long-wavelength radio emissions from the cosmic dark ages — the era between the Big Bang and the formation of the first stars — that are blocked by noise pollution.

“Humans, as a species, are very noisy: We like our cellphones, we like our televisions, we like our computers, and all of those things emit a lot of noise at radio frequencies,” Lanz says. “If we had a telescope on the far side of moon, we could conduct some of the science that has slipped out of our reach just because of the noise humans make.”

But that is a wish for the farther off future; what Lanz is most excited for at this moment is the upcoming launch of the James Webb Space Telescope. For astronomers, engineers, and anyone remotely curious about the universe, the telescope’s launch, scheduled for November, heralds a once-in-a-generation event.

The largest and most powerful telescope ever built, it features a protective sunshield the size of a tennis court and an ingeniously designed mirror, comprising 18 hexagonal segments, that will unfold once it reaches space. Using infrared light, the telescope will allow astronomers to look back 13.8 billion years and see the earliest galaxies born after the Big Bang.

Lanz has been waiting for this launch since she first read about the telescope’s development. “I’m keeping my fingers crossed —I don’t want to jinx it — but it’ll be as big of an advance as Hubble was for understanding the history of the universe,” she says.

The recent surge of public support for these missions is gratifying for Shinn, who, like Gilligan, was asked more than once if NASA was “going out of business.”

Shinn always knew the agency’s mission was intact. He’d gotten goosebumps when the Mars Maven spacecraft launched in 2013 on a mission to study the upper atmosphere of the red planet, and for years he’d seen the agency’s Earth-science programs benefiting citizens in real time, monitoring ocean temperatures to track rising seas, and using satellite imagery of forests to help fight wildfires. But the expansive missions currently underway are infectious for everyone.

In 2020, Shinn savored the moment as he watched a SpaceX capsule carrying astronauts to the International Space Station lift off from Kennedy — the first launch of American astronauts, on American rockets, from American soil since 2011.

“Everybody on the beach stood up cheering,” he says. “I felt so proud to be watching all these people get so excited for this launch. I had one of those moments, thinking, ‘We’re back. We’re doing something the U.S. has always been meant to do.’”

Picture: Mike Morgan

Posted on October 8, 2021