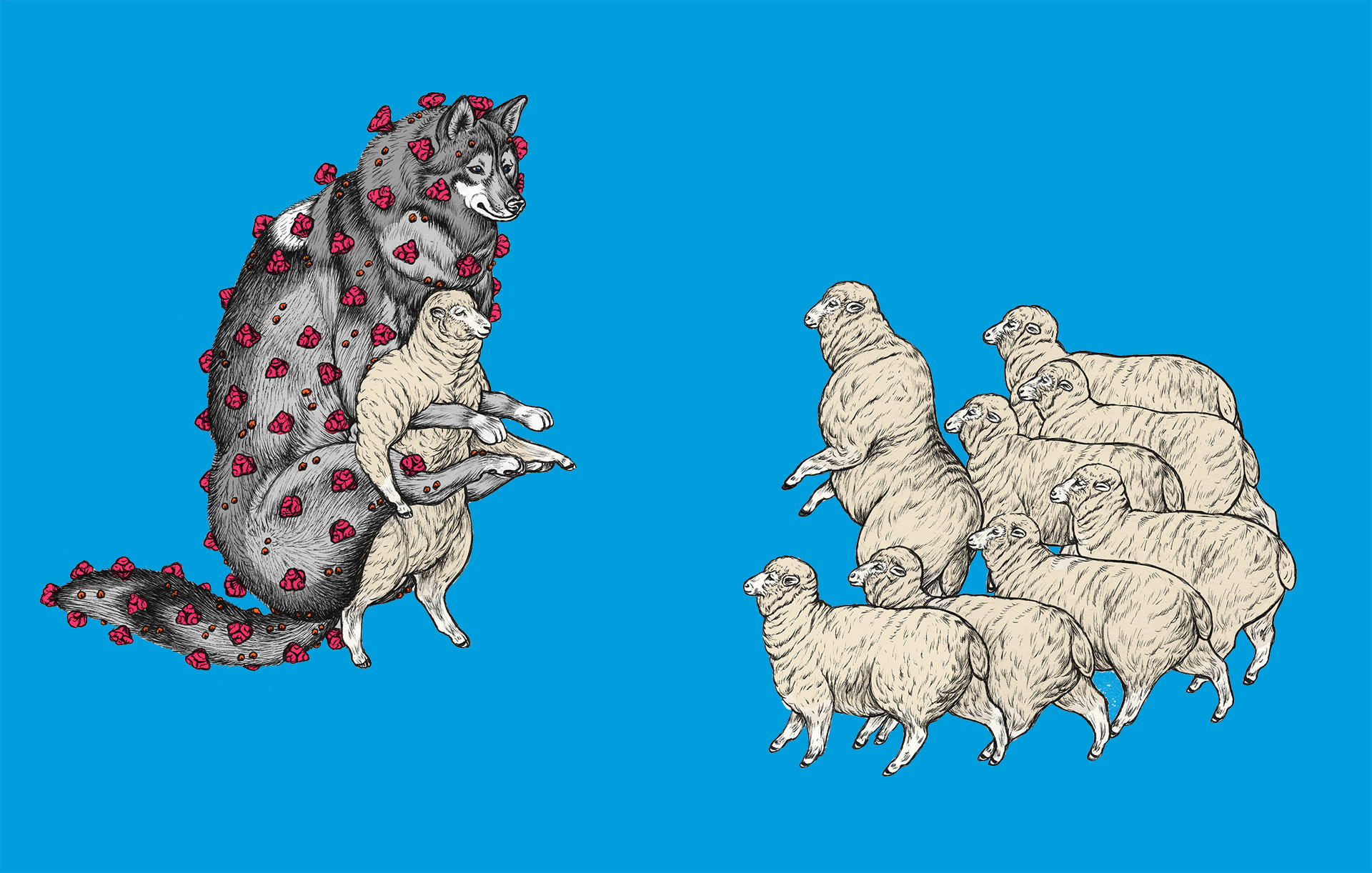

Political immunity

Two profs talk about the science and politics of vaccines.

Two TCNJ professors take a shot at explaining how a vaccine for COVID-19 has turned political.

When students and faculty were sent home from their classrooms last March, Amanda Norvell, TCNJ biology professor and interim dean of the School of Science, understood that a vaccine, specifically a SARS-CoV-2 vaccine that would protect against COVID-19, would be an important step in returning to normalcy. And to have that vaccine within a year, she thought, would be “pretty miraculous.”

Yet, by the close of 2020, pharmaceutical companies Pfizer, Moderna, and AstraZeneca reported that their COVID-19 vaccines were not only safe, but effective beyond expectations. Norvell, who teaches classes on the biology of human disease and prevention, was excited: The vaccines were promising in their own right and also were proof of concept. That is, they could elicit an immune response against an invading pathogen — like a virus — training the immune system to fight off that invader in the future.

The leading COVID-19 vaccines vary in terms of how they’re delivering coronavirus proteins into your immune system, but almost all are targeting the same molecule on the virus, the spike protein, which is found on the outside of the virus. “It’s great news that the immune response directed at the spike protein confers protection,” Norvell says, adding that it will help with the development of other vaccines in the future. “These pharmaceutical companies are reporting efficacy rates of 90%, which is pretty amazing.”

Working together, the global research community made this discovery in short time. And the devastating prevalence of COVID-19 had an upshot when it came to vaccine trials: it meant researchers were able to gather more data quickly. For an expert like Norvell, this only inspires confidence. But while trust among the scientific community grows, there is also a rising tide of skepticism: In a STAT/Harris poll, one in three Americans said they would be reluctant to get a COVID-19 vaccine as soon as it was available. That could be a big problem in building herd immunity, Norvell says.

When most of the population is vaccinated against a pathogen, those who aren’t vaccinated or whose systems don’t respond to the vaccine are unlikely to encounter the disease, and the spread stops, Norvell explains. This pattern is known as herd immunity. “In class, we talk about how your choice to not vaccinate doesn’t just impact you. It can affect individuals who are non-responders, those who are immunocompromised, and even babies,” she says.

“As someone with a background in immunology, but also as a patient and a parent, I trust that any vaccines we get have had enough testing to determine safety,” Norvell says, adding that adverse effects that remained undiscovered after a trial are a “lightning strike” of a possibility, too improbable to even consider. But, she says, anti-vaccination groups seize upon and inflate this sense of danger, overshadowing vaccines’ well-known benefits of protection.

Vaccine skepticism is not new — the first American anti-vaccination activists appeared on the record in the late 1870s — but the movement’s reach has gained notable ground since 2016. Norvell speculates that one reason for this growth in anti-vaccine sentiment is social media, which makes it easy to disperse misinformation under the guise of credibility. In her classes, she shows her students how groups with objective and official-sounding names sow skepticism online and encourage people to circumvent public safety measures. But in 2020, politics also played a role.

According to TCNJ Political Science Department Chair Daniel Bowen, when an issue breaks along such a stark party divide, it may well have less to do with the issue at hand, and more to do with how leaders shape public opinion.

“At the beginning of the pandemic, we did see some unification around communal support of one another through preventive measures against COVID-19, but there were other messages activated and framed in terms of liberty, distrust of government, and distrust of big business,” Bowen says. Sometimes, this was for short-term political gain, he says, but it may do long-term damage.

“Distrust of government is certainly a long-standing thread in American politics,” he adds. “The difference more recently is that that distrust has become starkly partisan,” with each side doubting the leadership of the other. “We’re at the point where we’re in a crisis and we need corrective action, but the lack of trust is out there undermining our ability to fight a pandemic,” he says. “It really does harm our ability to act collectively to solve a problem.”

The vaccine debate has become a key element of this partisan conflict. Recently, the political right, with its concern for personal liberties, has increasingly incorporated vaccine opposition into its platform. In spring 2019, while the U.S. was weathering the most severe measles outbreak since 1992, Republicans rejected six Democrat-supported state bills to tighten vaccination requirements for school-aged children. Further, they introduced legislation to make vaccination requirements less stringent in two more states.

But Bowen is optimistic vaccines will be returned from political opinion into the realm of evidence-supported science. One source of this optimism is that before losing the presidential election, Donald Trump celebrated the development of an effective COVID-19 vaccine through Operation Warp Speed and then delivered it to patients as a landmark achievement for his administration.

“If Trump used the federal government to help develop the vaccine, and President Joe Biden uses the federal government to help disseminate it,” Bowen speculates, their bipartisan investment could help to diffuse some of the politicization and build trust — both in the government’s purpose of serving the people, and in the solutions they offer.

According to Norvell, vaccine adoption is America’s path to herd immunity, so trust in vaccines — especially a COVID-19 therapy — can’t come soon enough.

Illustration: Tim Enthoven; Photos: Peter Murphy

Posted on February 11, 2021