‘One Short Day’ inside Broadway’s Emerald City

On stage in New York City’s Gershwin Theatre, Glinda and Elphaba—the star witches of the “Wizard of Oz”-inspired musical “Wicked”—sing and prance their way through the Emerald City. Fifteen feet above the action, Christy Ney ’99 flips light switches and taps her feet and fingers in time to the music below, speaking quiet commands into a microphone headset. As the blockbuster musical’s assistant stage manager, Ney is charged with orchestrating the look, sound, and feel of “Wicked.”

On stage in New York City’s Gershwin Theatre, Glinda and Elphaba—the star witches of the Wizard of Oz-inspired musical Wicked—sing and prance their way through the Emerald City. Green lights flash in time with cymbal crashes. Actors in outrageous costumes high-kick, handspring, and bicycle across the stage. Giant scenery glides back and forth as hundreds of tiny marquee lights flicker.

Inside a cramped black booth some 15 feet above the action, Christy Ney ’99 flips light switches and taps her feet and fingers in time to the music below, speaking quiet commands into a microphone headset. Her words are broadcast throughout the theater to a host of behind-the-scenes people: carpenters, electricians, a spotlight caller, automated scenery runners. From inside the booth, it winds up sounding like this:

Cast, on stage: “One short day in the Emerald city—”

Ney, into headset: “Lights 156.5—go.”

Cast: “One short day, full of so much to do.”

Ney: “Lights 158.5—go.”

“What people don’t get to see,” Ney muses during a brief break, “is that while the cast is performing on stage, I’m also doing my own little performance up here.”

As the blockbuster musical’s assistant stage manager, Ney is charged with orchestrating the look, sound, and feel of Wicked. “The purpose of this job,” she says, “is to make sure those three aspects stay exactly as the creators intended.” It’s no small undertaking, considering this show opened nearly a decade ago, and no small responsibility, considering it has been the highest-grossing Broadway production every year since. (Lest you suspect Wicked’s blockbuster status is fading, note that it set a new Broadway box-office record just one week before this performance, grossing $2,947,172 between Christmas and New Year’s Eve.)

From her hidden perch on the theater’s far left side, Ney cues actor entrances, lights, scenery changes, and even sound effects. “We run the show,” she says of herself and the show’s other stage managers, who are currently stationed on the left and right stage wings. “We are the center point of communications for the entire production side of Wicked, or as my dad so poetically put it when he came to watch me work one day, ‘I guess without you doing this work those actors would just look like a bunch of poops on stage.’”

While this afternoon’s performance runs unblemished, there have been mishaps in the past—unavoidable when you’re performing a live two-and-a-half-hour musical more than 400 times a year, inevitable when that musical is the special-effects-laden Wicked. In the grand tradition of theater superstitions, Ney balks when asked about past calamities while the show is underway. She’s willing to discuss them a few days later over the phone.

There was once a debilitating brownout during the high-tech “One Short Day” number. Those crucial headset connections have dropped out at times or only allowed one-way communication. The one-ton-plus Wizard of Oz head once got stuck on stage and required five male crew members to come drag it off. “When something like that happens, what you want to do is say, ‘Let’s just pull the curtain and stop the show,’” Ney says, “but really the old adage is true: The show must go on.

“I take calling the show extremely seriously,” she adds. “While I don’t necessarily get butterflies like I did early on, I still feel a rumble all day long if I know I’m going to call the show. You have to be completely ‘on’ for those three hours. You can’t let your brain stray because you’re in control of how everything looks and sounds, and people are counting on you. And you’re up there completely alone, so I try to get enough sleep, go easy on cocktails the night before, and not eat anything too strange that day.”

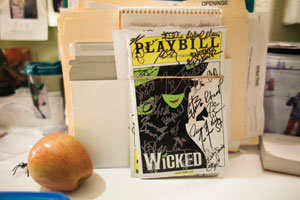

With six evening shows and two matinees per week, Ney works long days and odd hours. Today, she arrived at the theater around noon, printed up a sheet of cast substitutions, called a building manager to see about getting the heat lowered—Wicked’s smoke effects can envelop front-row audience members if the theater’s temperature is off—nibbled on some apple slices and spoke with each production head about those cast substitutions. After climbing a steep ladder staircase to spend three hours “calling” the show from her little booth, she will climb back down and return to a windowless third-floor office—it looks like a dressing room, but with laptops instead of makeup palettes—to record a postshow report. Then she’ll grab a quick dinner break and start the whole thing over again for the 7 p.m. performance, finally catching the bus home to Union City, NJ around 10.

“We’re working six days a week, 365 days a year,” she says. “That part can be hard. You can’t make it to weddings; you miss Bar Mitzvahs. Saturdays are the longest. I leave the house at 11 a.m., and I’m not home until 11:30 p.m. But I’m also really lucky. I get to put on a play every day.”

Though she doesn’t do a lot of it in her stage-managing role, Ney says that she “popped out of the womb singin’ and dancin’.” At 3 ½, she asked her mother to enroll her in dance classes. A few years later, she saw her first live performance—a touring production from the kids’ TV show The Magic Garden—and around age 9, her first stage musical: a local high school’s production of Grease. “I remember just being totally blown away,” she says of the latter. “They had a real car up there on stage! I was thinking, ‘I know this show isn’t real, but that car is real.’ It was simultaneously confusing and exciting.”

She nurtured her love of theater as a television/theater production major at TCNJ. In 1996, a trip with friends from TCNJ to see Rent on Broadway left Ney in awe. “I was just like this the whole time,” she says, dropping her jaw and widening her eyes. “That was the show that made me want to do this job.” She got her first chance to try it during a campus production of Sweeney Todd, for which she ran the “Pie Shop Crew.” “I called the cues for when the pie shop would rotate,” revealing another piece of the show’s scenery. “That was really my first taste of heading anything like that. It was my first taste of, ‘I can do this. I can manage what goes on behind the scenes.’”

After graduation, Ney moved to New York and began performing the classic struggling-artist shuffle. She temped during the day and worked as a production assistant for various shows and events at night. Eventually, she landed a job as assistant stage manager for the first national tour of The Lion King. Four years later, just days after giving notice that she was leaving the road, a former colleague called. Would she like to come do the same job for Wicked? It was April 2007; she’s been helping to run Wicked eight times a week ever since.

Back in the Gershwin Theatre, as the actors take their final bows, Ney’s above-stage show continues. She calls out more spotlight cues and, following a standing ovation, directs the house lights to spring on. Then she carefully packs away her props—the headset, a bottle of water, a paper on which she’s recorded that the show finished five minutes earlier than usual today—and turns out each tiny light in her booth. Her own performance complete, she slings a tote bag over one shoulder and climbs back down the steep ladder steps onto the darkened stage.

All photos (c) Don Hamerman.

Posted on March 4, 2013