College in Prison

TCNJ students are taking class side by side with inmates at a correctional facility through a program that is ending recidivism and providing transformative experiences for everyone involved.

We’re in prison, sandwiched between two barred iron gates, so why doesn’t anyone else look nervous?

The college students around me chat about final exams and which classes they’re taking next semester. No one mentions the prison guards following us or the voice that yelled something—it was hard to make out specifics, but it didn’t sound friendly—from one of the prison’s windows on our way in.

I’ve received loads of information about what not to do here. Don’t wear orange or khaki. Don’t discuss an inmate’s past. Don’t bring in a cell phone or even a retractable pen. But I haven’t heard anyone address the biggest question: What if something dangerous happens?

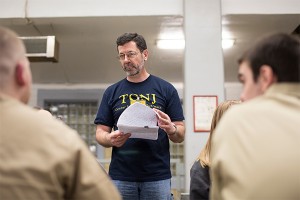

Though he masks it well, there’s at least one other person in this group who’s also anxious. Professor Glenn Steinberg has been bringing his literature class to the Albert C. Wagner Youth Correctional Facility in Bordentown every week since January, but he still worries. The tense feeling usually creeps in over the weekend and takes a firm hold on Monday morning. “It’s stressful being the professor,” he says, “and knowing that I need to overcome any administrative situations and keep a cool head and face if anything odd or unusual happens so the students don’t freak out.”

The heavy gate separating us from the prisoner area swings open and we’re led down a concrete hall and into the prison cafeteria. It’s crammed with four-seater stainless-steel tables and it smells sour, like rancid milk mixed with cheap disinfectant. The TCNJ students settle in a long row on one side of the metal tables. Two prison guards in police-blue uniforms watch closely from the back of the room.

There’s more generic college chit-chat until someone spots the inmates, dressed in khaki jumpsuits, walking in through a different iron gate. They sit down on the other side of those metal tables, directly across from their TCNJ counterparts. The two sets of students smile at each other, exchange hellos, and spread out their books and papers and folders.

They’ve met for class eight times now and have gotten friendly — though not overly so. As sophomore Stephany Sakharny puts it: “I’ve found that I have a lot in common with [the inmate students]. It’s like we could have been friends in another life.”

After a quick wrap-up of the previous reading assignment, Steinberg strides to a whiteboard in the center of the room, grabs a black marker and writes out the opening lines to Dante’s Inferno in their original Italian:

Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita / mi ritrovai per una selva oscura, / ché la diritta via era smarrita.

Midway along the journey of our life / I woke to find myself in a dark wood, / for I had wandered off from the straight path.

* * *

Sitting on the TCNJ side of one table is Sara Stammer, a friendly sophomore with an already-crowded resume: double major in English and women and gender studies; double minor in criminology and psychology; class representative on the Student Finance Board; member of the English honors society; columnist for The Signal.

Her resume practically sparkles.

“I was looking for one of those college experiences people talk about — the things you can’t do in everyday life,” she says. “I figured going to prison and taking classes with inmates was one of those things.”

After spending most of the day in other classes, Stammer hopped in a shuttle van outside Loser Hall with the rest of her Classical Traditions classmates at 5 p.m. At A.C. Wagner, after exchanging her driver’s license for a visitor’s pass, sending her belongings through an X-ray machine and spreading her arms for a metal-detector wand, Stammer finally made it to this beige cafeteria.

After spending most of the day in other classes, Stammer hopped in a shuttle van outside Loser Hall with the rest of her Classical Traditions classmates at 5 p.m. At A.C. Wagner, after exchanging her driver’s license for a visitor’s pass, sending her belongings through an X-ray machine and spreading her arms for a metal-detector wand, Stammer finally made it to this beige cafeteria.

The whole process absorbs almost four hours of her Monday nights, but she’s never missed a session. “The corrections officers told us that one of the most important things we can do is be consistent,” she says. “The last thing [the inmates] need is for us to only show up sometimes or to not take the class seriously. And just knowing I only get 15 chances at this” — Classical Traditions meets at A.C. Wagner 15 times over the semester — “I want to make sure I make the most of coming here.”

By the first of those 15 visits, Steinberg’s TCNJ students had already gone through two orientations, during which the prison staff rattled off rule after rule and cited danger after danger. “I think they were trying to scare us, and as a result, we expected the worst,” Stammer says. “But then we got here the first night and the inmates came in to join our class. They were smiling and asking us how we were. We knew it wasn’t going to be this creepy us-versus-them environment. We’re all just classmates studying the same literature.”

Run through the College’s Center for Prison Outreach and Education, the College in Prison program has been offering these combined TCNJ-inmate classes at A.C. Wagner since 2009. This time it’s Steinberg’s Classical literature class; other semesters it’s been criminology, history, sociology.

Both the Wagner and TCNJ students will receive college credit for completing Steinberg’s course. They’ll read The Odyssey, The Aeneid, The Metamorphoses and Dante’s Inferno. They’ll write papers and take exams, including a midterm and final.

Steinberg distributed the graded midterms last class. One of the Wagner students had the highest score: a perfect 100 percent.

“I definitely was surprised with [the inmates’] preparedness and their ability to understand the material,” says Kevin Alexander, a senior psychology major in Steinberg’s class. “That’s not to say I didn’t think they were going to understand the material, but….several [inmates] in the class consistently say things that make me go, ‘Wow, this guy is just so smart.’ It makes you think, ‘There but for the grace of God go I.’”

“Many of them are very bright,” Steinberg echoes. “In some ways, it breaks your heart to see these guys in prison who are clearly very smart and very curious about their world and what they’re learning.”

They’re also “very typical of TCNJ students,” Steinberg says. “There are students who are really passionate and committed, and there are students who are interested and engaged sometimes, but not always.”

Of the seven inmates in class tonight, most have already taken multiple college courses in prison. One guy tells me it helps “normalize the experience” of being there. He was partway through school at a nearby community college when he came to Wagner. With these classes, he’ll be able to finish his associate degree soon. Maybe he’ll go to Rutgers University after he’s released.

While the inmates and TCNJ students chat together during their mid-class break — and occasionally while Steinberg is trying to teach them — past offenses remain off-limits.

“Some of the inmates, even in our class, are violent criminals,” Alexander says. “But at the orientations, they told us not to ask what they did and also not to worry about it. The last thing they want to be thinking about in class is why they’re in prison and how they got there. It’s three hours every week when they can just forget about that. Why should I ask why they’re there if they don’t ask me why I’m there?”

* * *

The United States tops the rest of the world in the percentage of its citizens who wind up in prison. According to Bureau of Justice statistics, 2,239,800 American adults—one in every 107 men and women—were incarcerated in prison or jail in 2011. (Nine years earlier, in 1992, it was nearly half that: 1.3 million.)

About a thousand of them, all men ages 18 to 34, are currently housed in the Albert C. Wagner Youth Correctional Facility in Bordentown, New Jersey.

A.C. Wagner is on the left side of the road, a mile and a half off Route 130, just past a large cow pasture. Across the street, the town’s “Friendship Fields” are often filled with Little Leaguers and their grinning parents or young soccer players and more grinning parents.

There are several security watchtowers throughout Wagner’s parking lot, but the buildings themselves are simple, multi-story red brick — not unlike an office building or high school. Only the tall fences and barbed wire clarify its use as a state-run, medium-to-maximum-security prison.

There are several security watchtowers throughout Wagner’s parking lot, but the buildings themselves are simple, multi-story red brick — not unlike an office building or high school. Only the tall fences and barbed wire clarify its use as a state-run, medium-to-maximum-security prison.

Celia Chazelle, a Medieval history professor and chairwoman of TCNJ’s Department of History, discovered A.C. Wagner while researching prisons five years ago. At that time, she was examining the lack of prisons in early Medieval Europe.

“They maintained social order without a focus on the prison,” she explains now, “and I was interested in that tremendous contrast with the way we do things. I thought maybe studying the medieval system could help us rethink our current approach.”

But Chazelle had never been inside a prison, and that seemed like an important step in her research process. She signed up with the Petey Greene Prisoner Assistance Program—a newly formed group in Princeton that was sending volunteer tutors into A.C. Wagner.

When she entered the prison for the first time in June 2008, “I had all these preconceptions about it,” she says. “I mean, some of them are accurate. Prisons can be places of violence, they’re very harsh, you don’t question authority, that sort of thing. But at the same time, what I had not been expecting was this level of intellectual engagement and interest and the courteousness of the prisoners I was teaching. They were very grateful and very eager to do the work.”

Through her tutoring visits, Chazelle became friendly with Wagner’s administrator, TCNJ alumnus Alfred Kandell ’83. She told him how much she enjoyed tutoring and said she wanted to do something bigger to help. Kandell encouraged her to teach a non-credit college course in the prison and eventually Chazelle agreed. She would lead a group of carefully selected inmate students through the same freshman seminar she was teaching at TCNJ that semester: Social Ethics.

She chuckles now, acknowledging the irony. Then she adds: “It turns out the Wagner students have very developed, very carefully thought-out ideas about ethics. They were quite conservative, actually—much more conservative than the TCNJ students.”

Soon Chazelle was incorporating TCNJ more directly into her classes at Wagner. In 2009, she launched the College in Prison program, which places TCNJ and Wagner students side by side for combined classes taught in the prison. The program falls under the College’s Center for Prison Outreach and Education, which Chazelle co-directs. She taught the first combined class herself—The History and Culture of Prison.

“I was sure the [College] administration would say no,” she adds. “Send our students to prison? You’ve got to be kidding! But they were very open to it.”

And it was soon clear that, for the TCNJ students, “this is such a transformative experience,” Chazelle says. “It’s so much more powerful than anything you can give them in the classroom. I love to watch them change over the semester. Instead of having an amorphous view of prison statistics, they get to know these individuals as classmates, and very often, they start questioning the American prison system.”

* * *

A.C. Wagner houses only a fraction of New Jersey’s inmates—a population that hovers around 23,000.

According to the New Jersey Department of Corrections’ Office of Transitional Services, the average person leaving a state prison like Wagner is a single (83 percent), black (63 percent), 34-year-old man who has spent two or three years behind bars.

And there is a one in three chance he’ll be back.

OTS reports that 55 percent of inmates released from a New Jersey prison are rearrested, typically within nine months. The state’s former inmates are re-convicted 42.7 percent of the time and about a third of them end up back in prison.

Multiple studies have shown that uneducated inmates are the most likely to be re-incarcerated—and in fact, OTS claims that returning offenders, on average, read at a sixth-grade level and have a fifth-grade math level. Two-thirds have no GED or high school diploma.

Multiple studies have shown that uneducated inmates are the most likely to be re-incarcerated—and in fact, OTS claims that returning offenders, on average, read at a sixth-grade level and have a fifth-grade math level. Two-thirds have no GED or high school diploma.

“A lot of these inmates ended up where they did because the education system failed them,” notes Rebecca Li, a TCNJ sociology professor who taught the combined course Self and Society at Wagner last fall. “In my class, many of them talked about a common story: They went to school and the school was not teaching anything. It was boring, so they began getting in trouble. When they got in trouble, they were labeled as troublemakers. Then they got kicked out of school or dropped out, which is how they got in with the wrong crowd and ended up in prison.”

While some gripe about the college education these inmates are getting free of charge—Steinberg has seen “friends” on Facebook share posts about how great prison must be, stuff like Free food and brand-new gyms? Sign me up. — Chazelle says the benefits of College in Prison are farther-reaching than most people realize.

“These guys are locked up in a facility that offers them nothing above a GED right at the time they should be getting job skills and vocational training,” she says. “Right there, that’s a life sentence you’re giving them for poverty. It’s also adding to recidivism. You’d think if we’re going to lock them up for a decade, we’d want them to come out more capable of functioning in society. Instead, they’re often forced to go right back to the life that got them in trouble initially.”

Li speaks of the intellectual confidence that inmates build by taking college courses — a confidence that may encourage them to pursue college degrees when they leave prison — and Chazelle says there are about 50 current Rutgers University students who have come from the prison system, including a few from Wagner.

In 2012, Rutgers senior Walter Fortson was selected as a Truman Scholar — a national award that includes a $30,000 scholarship for senior year expenses and graduate school studies. Only a few years earlier, Fortson was in prison for selling crack cocaine. He began taking classes at Rutgers while living in a half-way house in Newark, awaiting parole.

“A number of the guys I’ve taught at Wagner have said they never thought about college before they were incarcerated,” Chazelle says. “Not all of them can go on to a four-year school, but [taking these classes] also increases their chances of employment. It lowers their chance of recidivism. It makes them better fathers.”

With those benefits in mind, TCNJ, Rutgers and five other New Jersey colleges and universities teamed up to create the New Jersey Scholarship and Transformative Education in Prisons Consortium last year. “Our vision,” the NJ-STEP website announces, “is that every person in prison who qualifies for college [will] have the opportunity to take college classes while incarcerated and continue that education upon release.”

“We approached a group of major benefactors who were looking to fund a state-wide initiative that could then become a national model for prison education,” Chazelle says. “NJ-STEP has made New Jersey that model.”

The Ford Foundation and the Sunshine Lady Foundation each committed $2 million to support NJ-STEP through 2016. “A host of studies of higher education in prison demonstrate that this is one of the best ways to reduce the recidivism rates of people who are sentenced to prison,” the NJ-STEP site says. “While we are dedicated reformers who share a vision of social justice, we also know that by expanding the opportunities for college in prison, we reduce the rate of correctional failure, increase public safety, and in the long run reduce the costs of prison.”

* * *

It’s been a long semester for Glenn Steinberg—a soft-spoken scholar with a professorial beard and glasses. He says he likes teaching the inmates, but administrative issues keep popping up, especially around location. At first Classical Traditions was put in the auditorium, then about a month ago, it was moved to the prison cafeteria, which swallows the voices of Steinberg and his students but magnifies every passing garbage cart or jangling set of keys.

Then there are all the rules. Steinberg and his TCNJ students have to wear loose-fitting clothes. Their tops can’t show any shoulder or lower-back skin and their jackets and sweatshirts can’t have hoods. Their notebooks can’t have spiral bindings and their pens can’t have springs. One student set off the metal detector this semester by wearing an underwire bra. Another had to miss class because she’d forgotten to bring a photo ID.

A few weeks ago, a blaring alarm interrupted Steinberg’s lecture. There had been a medical issue in the prison gym, but the TCNJ students were whisked away from their inmate classmates and taken to a separate location.

“It’s been incredibly challenging,” Steinberg says, “but if there was an opportunity to do to this again, I’d jump at the chance.”

As would Sara Stammer, the sophomore student. “If I could,” she says, “I’d take this class over and over again.”

They may not have that chance, though. Chazelle says with some sadness that these courses are in jeopardy “because the Wagner administration has changed and is now much more security-concerned.” For the first time in eight semesters, the College will not offer a combined Wagner-TCNJ class at the prison this fall. “We have to get these issues sorted out,” Chazelle adds. “Not every professor would be as patient as Glenn has been this semester.”

But tonight, it’s still spring. Steinberg’s combined class is only halfway over and—though some have “wandered off from the straight path”—the Wagner and TCNJ students are, as Stammer put it, “all just classmates,” sitting together in a drab cafeteria, jotting down notes about the opening lines of Dante’s Inferno.

All photos (c) Dustin Fenstermacher.

Posted on September 10, 2013